Memory-Machines

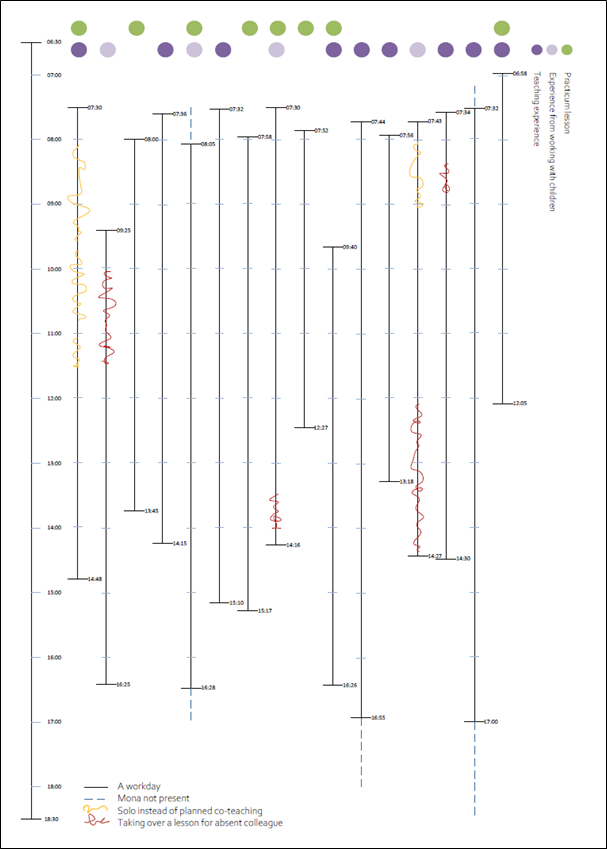

The mapping in this molar mosaic offers the duration of a becoming-teacher workday and whether one has prior experience of work in institutional settings. By returning to the events from the day of the visit, the overview also illustrates the capriciousness of school life where becoming-teacher unexpectedly is asked to teach solo or cover for an absent colleague on the day of the visit. The overview also relates whether becoming-teacher is offered the stipulated practicum lesson during the day of the visit.

Before going into specifics and the question about ‘prior experience’, a reminder of the Deleuzian take on the relation between past and present to see how this relation becomes a more multifaceted question.

Past and Present

Past and present ‘coexist’. Instead of a present that moves into a vanishing past, it is the other way around; the past precedes the present, and the past is ‘contemporaneous’ with the present. This paradox – that only the past is whilst the present was (Deleuze, [1966]1988) – affects what we come to mean when we examine a workday and ask if becoming-teacher has ‘prior experience’. Especially, if we by ‘prior experience’ refer to a specific part of one’s past, such as ‘paid work in a school’. If only actualizations of our virtual pasts were as well-behaved as we make them out to be.

A workday taken as ‘contemporaneous’ with its past, suggests that the undone subjects should be gathered as a patchwork of transmutational memory events. One’s history becomes a resource that is plugged into the unfolding present in unforeseen ways.

When past and present coexist, Lortie’s well known problematization of ‘the apprenticeship of observation’ ([1975]2002) becomes not only reasonable but unavoidable[1]. In fact, the affective traces on bodies that have partaken not only in various school assemblages (my concept, not Lortie’s), as a pupil, a parent, a classroom assistant, but in innumerous non-educational assemblages, suggest that the slivers of past we recognize as someone ‘having experience’, must be gathered as coarse reductions. Yet, recollecting is neither obedient nor tame as it leaps and pulls to mix from different levels of an entire lifetime and beyond[2]:

For Deleuze […] an ethical education is one that involves not simply our minds but our lives, taking it to places it has not gone and did not know were there. And, indeed, those places are not there until they are created from the virtual out of which we live. (May & Semetsky, 2008, p. 154)

A different way to think of the past is to think of ways to create encounters that activate all aspects of life. Ask instead how life might be. Offer your Lortie-apprentice new vistas!

But the tricky thing with memories is that past-leaping is sometimes actualized as recognition and sometimes as creativity, where the latter enables an escape from the dogma of habitual thought and action. Thanks to this virtual past that co-mingles with the present, bodies have the potentiality of becoming-other:

If we are composed not only of the actual but also of a virtual difference, then who we might be is not divorced from who we are. To become who we might be is not to become something other than ourselves; rather, it is to become something other than our actual selves in the process called by Deleuze becoming-other. ([italics in original] May & Semetsky, 2008, p. 152)

‘Becoming-teacher’ is this ‘becoming-other’, an opening that does not have to match or go in sync with our past nor our images of ourselves’; instead, the body as memory-machine comes with inexhaustible recollection combinations where some work favorably in ways that come to augment our capacity to act in the present, other come to diminish our capacity to act.

Becoming-teacher must therefore be taken as ‘non-linear’ processes (e.g. Strom & Martin, 2017; Adams, 2021; Strom & Viesca, 2021) that dishevel illusions of time as ‘linear’ and change as synonymous with ‘progress’. Every encounter therefore becomes an opportunity for a body to calibrate different times and ignite memory-machines to plug into unforeseen regions of the past. So, what constitutes ‘having experience’ is best answered retrospectively when actualizations offer clues as to what resources becoming-teacher mobilizes to work with-in presents.

Ensuing mapping therefore shows the duration of a becoming-teacher workday and prior experience of work in institutional settings. The mapping in this molar mosaic also shows bodies that unexpectedly are asked to teach solo or have to cover for an absent colleague on the day of the visit. We also get to learn whether becoming-teacher has the stipulated practicum lesson on the day of the visit[3] (more about the notion of ‘practicum lesson’ in upcoming section).

The below illustration offers a molar perspective on teacher becoming (to investigate the diversity of a workday, go to molecular mosaics suggested in paratheses). The linearity of time disavowed in the above discussion is temporarily resurrected in the below overview, but is thoroughly undone in the many mosaics (e.g., go to mosaics Quizzing, Oh…, Two Hours before Fucking Whore, and Themes on a Silence).

A Workday

Illustration

1: A Workday

Working Hours

The above illustration (Illustration 1) offers the duration of a becoming-teacher workday, green dots, whether they have their weekly practicum lesson on the day of the visit, and purple dots the matter of prior experience (which is distinguished as working with children (preschool and/or extended school), or teaching.

The duration of a workday differs from one day to another, as does what tasks becoming-teacher is to do. There is also a difference in duration and workload between different becoming-teacher assemblages; whilst one becoming-teacher has a four-and-a-half-hour workday, another has a workday that amounts to eleven hours and seventeen minutes[4].

Besides asking if I can come visit on the day of a practicum lesson (which we will come back to in the section on ‘practicum lessons’), there are no other requests regarding what to see, when to visit, or for how long. On the contrary, the Deleuzian supposition is that every moment is singular, each encounter a potentiality. Put differently, there is no such thing as what teachers ‘normally’ do or how long a workday ‘ought to be’ since everything that unfolds as a workday becomes a becoming-teacher workday.

The shortest of the mapped workdays is accordingly four hours and thirty-five minutes. This becoming-teacher schedule matches neither that of the supervisor nor that of the children on the day of the visit. Instead, becoming-teacher leaves for the day before everybody else. At times actualizing and becoming actualized as one of the other learners in this school, becoming-teacher can be seen staying in the supervisor’s proximity – just like so many of the other learners. In corridors, becoming-teacher hangs the jacket next to the children’s, not next to the other colleagues; becoming-teacher takes off the shoes and walks around in socks inside the classroom like the rest of the class, in contrast to the supervisor whose outdoor shoes clap against the linoleum floor. And when it is time for the school’s morning staff meeting, becoming-teacher is the last to be informed that it has been cancelled (go to mosaic Holy Grailing).

Class Mentor

Twelve becoming-teachers work as ‘class mentors’. Being a class mentor encompasses handling all the administrative responsibilities of the teacher, such as keeping guardians updated on their child’s social situation and learning development, answering emails, organizing parent-school meetings, participating in meetings with other supportive functions, setting up individual development plans, handling action programs with colleagues[5], and so on. The majority of becoming-teachers share this responsibility with a colleague or supervisor.

Two becoming-teachers share a class with another becoming-teacher, a third has a shared mentorship with another colleague where the class has been divided into two, meaning that becoming-teacher is alone with one group. Organizational conditions, workloads, and who is to do what changes rapidly. A becoming-teacher says, in between tasks, that there “was supposed to have thirteen children in a class to mentor, but in reality I have thirty” (B, p. 1). The reason for the changed circumstances is explained as an effect of the staffing situation:

Becoming-teacher and supervisor explain the staffing situation, they want me to write about this. There was supposed to be six teachers [i.e. full-time equivalents] and ninety pupils, they tell me, and at the moment there’s only three and a half – two more are expected to come later this year. Today there are two sick, which means there are only two and half teachers – one of whom is a physical education teacher who works in the other building. (B, p. 10)

Thus, there was a staffing plan, but it fell through.

A closer look at the many sudden changes that dislocate plans.

Unruly Plans

Becoming-teacher is heading to the canteen when a child cuts in and asks; May I do a magic trick for you? Becoming-teacher says ‘Yes’and the walk is paused for the duration of the card trick. Wow!, becoming-teacher exclaims when the trick is finished before continuing to the canteen. (M, p. 3)

Cut off by a magic show on the way to the canteen; someone else has made plans to co-teach with a colleague but that colleague calls in sick; a third is about to start planning when instructed to take over a class for a colleague who has been called away on an urgent meeting; a fourth is scheduled for a staff’s meeting to register assessments into a digital system, or so the plan says – but plans change.

A change of plans can be expected. In fact, the only truly predictable facet of a workday seems to be the capriciousness of the present that have plans change. Take the case with the beforementioned staffs’ meeting where a principal has planned for teachers to register all children’s individual assessments into a new digital grading system. As soon as the principal leaves the room, the meeting draws a line of flight, that is, it trails elsewhere (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987). Colleagues instead take the moment to engage in an earnest and critical conversation about what it means to ‘know’ something, how children’s knowing is to be assessed, and how digital teaching materials affect teaching and assessment practices. Becoming-teacher partakes in this conversation as a voice within the collective assemblage of enunciation (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987); becoming-teacher’s voice is enacted and becomes ‘one of them’.

After Hours

The unruliness of plans is a way of (school) life, sometimes to the extent that impossible working conditions become camouflaged by (becoming-) teacher ‘flexibility’. One becoming-teacher and supervisor explain how scheduled “practicum lessons must be planned during evenings, after working hours, by email” (B, p. 1). Another how exceeded part-time work finds partial ease in the digital teaching materials used:

It is nice not having to spend time correcting work since these things are dealt with through the digital system – work already exceeds far beyond part-time work, becoming-teacher explains. (N, p. 7)

The fact that the digital teaching materials reduce after- hours work, is also the solution this group of colleagues later discuss as altering their teaching practices. Thus, a (becoming) teacher’s workday is unpredictable, and workloads easily go invisible since they have little correspondence to their official counterparts, namely schedules (go to mosaic Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock).

Retrospectively, a corridor magic show is forgotten and morphs into a question about whether one is on time for lunch to assist a colleague or not, just like lesson plans made after hours by text message are forgotten and morph into personal failure (see mosaic Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock). After all, solutions, such as stopping for a card trick or making plans late in the night, “do not resemble the conditions of the problem” ([1968]2014, p. 276); said differently, being late for lunch becomes a new problem that hides a potentially more urgent problem of there not being time for a corridor chat with an eager child wanting to show a card trick, just like a poor lesson plan may not be a problem about insufficient knowledge about how to do proper plans, but a problem about the conditions for planning. Thus, body-as-memory-machine is erratic and its machinic capacities both hope and hazard when actualized reality is forgotten and transmutes into an equally real (virtual) memory. The question is whether it is remembered that “the solution was as good as it could have been, given the way in which the problem was stated, and the means that the living being had at its disposal to solve it” (Deleuze, [1966]1988, p. 103).

Practicum Lessons

The practicum lesson is an educational element of the WITE-program. Practicum is presented as something that sets apart ‘work as learning’ from ‘regular’ teacher work. Practicum lessons are also part of the agreement between university and employer where the school unit has agreed to provide a supervised in situ session once a week where becoming-teacher attains mentoring on teacher- related activities. When planning visits, I have therefore asked if I can come to visit on the day of their weekly practicum lesson.

Of sixteen visited becoming-teachers, half of them have their practicum lesson during the day of the visit. Sometimes a missing practicum lesson has to do with banal reasons like forgetting they have agreed to shift days for their lesson. Other times it has to do with a supervisor being away on union-related matters, or a supervisor having a course of their own on the day of the practicum lesson. When things collide, practicum lessons are at stake.

On the day of the visit, three becoming-teachers had not had even one practicum lesson. Two becoming-teachers have their first practicum lesson on the day of the visit[6]. Regardless of whether becoming-teachers have practicum lessons or not, all are engaged in teaching on the day of the visit.

Visits suggest that practicum lessons are not an incorporated element in all organizations during this first semester of the program; sometimes because everyday life in school intervenes and plans go astray, in other organizations it has to do with school units not having enough staff to have two teachers in one classroom. Another obstacle is scheduling.

Use a friend’s way, the observed teacher instructs the class. Becoming-teacher is here to study twenty minutes of this math class. While children are using a friend’s strategy to solve the problem, the teacher colleague approaches becoming-teacher, and says that it is important to get hold of all the different strategies one can use to solve this problem. No one has yet ‘rounded up’, I’m still missing that one, the colleague explains.

As becoming-teacher is heading towards the door to go observe the supervisor’s class, the colleague hurries to catch up with becoming-teacher, quickly showing the materials they use and give a brief explanation to what becoming-teacher just saw the children doing. (I, p. 5)

In the above scene, we get to join a becoming-teacher that each week uses twenty minutes of their planning time to go observe a teacher colleague that the principal had originally assigned as supervisor. But due to this teacher’s overall workload, something had to go and it was decided that even if this person was the most suitable ‘supervisor’, this was the one task they could spare. Becoming-teacher was therefore assigned a new supervisor (go to mosaic, Following John).

The Diversity of Practicum Lessons

There is a diversity to how practicum lessons are actualized. Three becoming-teachers have their supervisor come observe them in situ and they take notes of unfolding events. Two of the three becoming-teachers thereafter receive feedback on the observed lesson, either in writing as part of a university assignment or in combination with oral feedback – like the below passage where a becoming-teacher carries out two consecutive lessons with feedback in between classes.

The supervisor approaches becoming-teacher and talks about what questions to ask and in so doing gestures towards the child who asked the question ‘What is the difference?’. The supervisor then adds that one could also have asked the class ‘What calculation method [should they use]?’. Becoming-teacher nods smilingly toward the supervisor, and immediately walks away to make notes in a notebook. (K, p. 3)

In the above setup, suggested adjustments are actualized in session two where they later discuss effects of said modulations (go to mosaic Holy Grailing).

In another school assemblage, a becoming-teacher actualizes the agreed- upon lesson as planned. However, the supervisor has forgotten that this is a practicum lesson and therefore comes and goes during class. So, whilst becoming-teacher is teaching, the supervisor seizes the opportunity to finish up on their own work. Becoming-teacher nevertheless wants response on the lesson, so just before the supervisor is about to leave for the day becoming-teacher asks for feedback. The surprised supervisor agrees to have the impromptu conversation. A lingering classroom assistant also joins in on the conversation and the two list the pros and cons of becoming-teacher’s lesson.

In yet another variation on a practicum lesson, becoming-teachers observe supervisors in action. The same becoming-teacher that spent twenty minutes observing a former supervisor teach arithmetic, is also seen taking notes in the new supervisor’s class. In these classes becoming-teacher combines note- taking with the role of assisting as a classroom assistant (go to mosaic Following John). A second becoming-teacher has a similar combination of observing and assisting, although here the supervisor sees the other adult in the classroom as an opportunity to divide the class into smaller groups for parts of the lesson, which leaves becoming-teacher alone again.

Prior Experience

Eight becoming-teachers have prior experience from teaching in compulsory school. Years even. Others have not been in a classroom since they graduated from school themselves, which means that they have been away from school for a few years. For two becoming-teachers it has even been (a) decade(s) since they set foot in a classroom.

Having prior experience of work in institutional settings plays out very differently in class (go to Two Hours Before Fucking Whore, Quizzing, Park of Silence, Oh… and The Backwards Booklet):

For this semester’s technology classes, becoming-teacher has been assigned planning time with a more experienced qualified teacher. The duo decides to go looking online for an assessment matrix to use for their upcoming classes. […]

The colleague reads from the matrix, “Explain the theme’s concepts”… What are “the theme’s concepts”?, the colleague asks.Becoming-teacher answers, “Force” and “momentum” are the theme’s concepts. […] The colleague asks again, Do they only have to know concepts for grade A? No, for all grades, becoming-teacher replies before adding, But they shouldn’t use “force” in all contexts. Becoming-teacher clarifies that they need to know ‘when’ to use ‘what’ concept. (N, p. 2-3)

As the above scene shows, being a becoming-teacher does not translate into ‘less knowledgeable’, just like qualified does not translate into ‘full-fledged’. Bodies in an assemblage can augment their joint capacities to act by actualizing affective powers connected to past experiences from teaching, or as the ensuing situation shows, from recent pasts such as university courses.

This becoming-teacher has planning time but decides to stay in the classroom to work with assessments in order to sit in on the colleagues’ weekly meeting:

Becoming-teacher glances between the stack of papers waiting to be assessed and the colleagues seated around the table, listens in on the conversation about individual development plans (IDPs). Becoming-teacher stops writing, asks a colleague a question about IDPs, and receives an answer. Becoming-teacher tells the team about a case from the university where a dissatisfied guardian turns to the teacher and requests five IDPs to five other children in the class. The question is whether you as a teacher would grant the request and provide five IDPs. The work team’s ‘no’ has becoming-teacher read out loud from lecture materials. The work team is told that the IDP after a performance review goes from ‘draft document’ to ‘official document’ which means that the teacher is required to supply the parent with the requested IDPs. (T, p. 10)

In the ensuing conversation everybody discusses what kind of information to put in an IDP. The meeting ends and everybody except supervisor and becoming-teacher exit; the two stay behind to carry out assessments and continue discussions about where to put what kind of information.

Taking Over Classes Impromptu

You are to become a math teacher, the supervisor insists when the becoming-teacher is reluctant to take over a colleague’s math class for a colleague who has been called away on an urgent meeting. Yes, is to become, becoming-teacher emphasizes before pointing out that becoming-teacher has never been alone with the sixth graders before. (P, p. 9)

The unpredictability of school life has already been indicated, but what is yet to be discussed is what happens when becoming-teachers are proposed as the solution to sudden staff shortages. For good or bad, colleagues do not differentiate between qualified teachers and becoming-teachers; if you are employed as a teacher, you become actualized as a teacher. Still, being asked to cover for a colleague minutes before class starts in a subject one has no knowledge about, seems an almost impossible task (go to mosaic The Music of (Air)plane-Math). Five out of sixteen becoming-teachers have to either ‘teach solo’, instead of co-teaching with a teacher colleague (go to mosaic Quizzing), or they have to take over lessons altogether for absent colleagues in other classes.

Out of the five becoming-teachers that need to change all their plans in less than thirty minutes in order to cover for a colleague, two are asked to take over subjects they admit feeling uncomfortable teaching. The above exchange involves a supervisor who insists that becoming-teacher should take over a class in a subject (math), grade, and group where becoming-teacher explains that they have no prior experience of. After some discussion the two decide that becoming-teacher should take the supervisor’s arts class, whilst the supervisor takes math. But the reason why becoming-teacher is asked to take the class is not because there are no other teachers available; instead, it is because the other colleague would have to skip planning time in exchange for teaching. Thus, the actualized solution shows how it is deemed preferable to send in an unexperienced and reluctant becoming-teacher into a classroom to teach, rather than have a colleague lose planning time – a decision rarely seen in law school or medical school.

Expectations

The staffsroom. Colleagues on a sofa. They banter over a cup of coffee. The supervisor, becoming-teacher and colleagues are joking about workload since becoming-teacher has just implied there is a lot to do now that becoming-teacher is a student – the supervisor laughingly replies, You only work fifty percent. (O, p, 6)

In an educational design where becoming-teachers work halftime and get paid for studying, comments in passing from some colleagues imply that they are considered as getting off easy. The fact that becoming-teachers spend the rest of the workweek studying does not enter these versions, nor that the becoming-teachers’ actual workweek exceeds that of the qualified teachers. Instead, comments emphasize that since becoming-teachers are employed as teachers, they are expected to do the same work as the rest of them.

Expectations put on becoming-teachers vary between school units and within a school unit. Some expectations are associated with whether becoming-teachers are familiar to the municipality and/or school unit, and if the organization ‘knows’ them as teachers from before becoming WITE-students. Becoming-teachers that are new to the school and/or are known as having little or no prior experience in teaching, are sometimes actualized as novices (go to mosaic Holy Grailing). Still, just like the scene with a novice in the above situation indicates, these designations are sometimes challenged by colleagues within an organization when becoming-teachers find out that they are expected to simply ‘be the teacher’.

What does it mean to ‘have experience’? Is it the number of hours spent in a classroom teaching that equals experience? Does it not matter whether becoming-teachers have access to supervisors and guidance? If not, then all becoming-teachers will come to ‘have experience’ in a semester’s time.

Actualized a Teacher

The staffroom, nine colleagues and the principal. Becoming-teacher sits quietly and listens. The principal starts the meeting and gives an account of teachers per work team and how many teachers there will be available for the ensuing semester. In the account provided, two becoming-teachers are listed as already qualified teachers. The two will accordingly be included in the schedule on the same premises as other qualified teachers.

Colleagues then go through what subject competencies colleagues without teacher certificates have, making a distinction between qualified teachers and becoming-teachers on the one hand, and colleagues who are not enrolled into a teacher education program but have other qualifications, on the other. (M, p. 9)

When organizing for the upcoming semester, this principal makes no difference between the two becoming-teachers and already ‘qualified teachers’. This incorporeal transformation comes to affect the workload for all involved. “In expressing the noncorporeal attribute, and […] attributing it to the body, one is not representing or referring but intervening in a way”, Deleuze and Guattari propose ([1980]1987, p. 86). It is not a question of true or false, or whether becoming-teachers have qualifications equivalent to those of qualified colleagues, for what the principal says intervenes in events. Becoming-teachers are assigned noncorporeal attributes equivalent to those of qualified teachers, giving colleagues the go-ahead to expect of becoming-teachers what they expect from other qualified colleagues.

But incorporeal transformations do not stay in the realm of language. Next semester this team will have fewer qualified teachers. Who is to supervise when becoming-teachers are actualized as qualified teachers? Knowing that it has taken months to get a first supervised session indicates that practicum lessons may become ever more difficult in the future with fewer colleagues to ask. And who do you learn from when your closest colleague is another becoming-teacher. And what about the children? One class will have considerably reduced opportunities to be taught by qualified teachers when two becoming-teachers are paired under the label ‘teacher’. Moreover, how will the organization provide support to learners if they have no way of knowing what goes on in classrooms (to explore the diversity of unsupervised lessons, go to mosaics The Music of (Air)plane-Math, Quizzing, Two Hours before Fucking Whore, Blank Maps, and Park of Silence).

Thus, what sections of the past a body comes to actualize in the thousands of unforeseen encounters of a workday is impossible to predict. Perhaps the more productive question might be to what extent bodies, school organizations, and WITE-programs affirm and find ways of utilizing actualizations of pastness as a resource in the unpredictability of presents.

Whether someone is said to have ‘prior experience’ of institutional work in school settings is not a reliable indicator of a body’s capacity to manage in new presents. Some becoming-teachers with prior experience of institutional work can be seen helping other qualified and more ‘experienced’ teacher colleagues with didactical questions (‘what is a theme’s concepts’) and juridical questions (‘what is the status of an IDP’), while other becoming-teachers with prior experience of institutional work find themselves alone with classroom assistants to solve seemingly impossible situations (go to mosaic Two Hours before Fucking Whore).

Thus, the length of one’s formal education or years spent working as a teacher is not a guarantee that one’s power to act in a school situation becomes augmented. Nor is prior experience a guarantee that one can manage all aspects of the profession. Instead, one’s powers to act change continuously. As Deleuze’s Spinoza has us know ([1981]1988), the question is how a body manages to put to work one’s virtual/actual resources in the unpredictability of school life.

Another question is under what circumstances, if any, a becoming-teacher can say no to teaching solo on short notice when employed as a ‘teacher’. School organizations sending unqualified teachers with no time to prepare to cover for absent colleagues seem to be one way of organizing for failure. The use of unqualified teachers is an established and at times unavoidable practice and one of the dire effects of the teacher shortages and unpredictability of school life, but the absurdity of this as a viable solution comes forth when envisioning the medical intern being sent into the operating room without preparation to perform a solo surgery, or the law apprentice being assigned to defend a criminal without having read the files. Patients and legal clients have rights to qualified help, what rights do learners (children and becoming-teachers) have?

References

Adams, E. (2021). Being before: three Deleuzian becomings in teacher education. Professional Development in Education, 47(2-3), 392-405.

Deleuze, G. ([1962]2006). Nietzsche and philosophy. Columbia University Press.

Deleuze, G. ([1966]1988). Bergsonism. Zone.

Deleuze, G. ([1968]2014). Difference and repetition. Bloomsbury Academic.

Deleuze, G. ([1981]1988). Spinoza, practical philosophy. City Lights Books.

Lortie, D.C. ([1975]2002). Schoolteacher: a sociological study. (2nd Ed.). University of Chicago Press.

May, T., & Semetsky, I. (2008). Deleuze, ethical education, and the unconscious. In I. Semetsky. (Ed.), Nomadic Education: Variations on a theme by Deleuze and Guattari. (pp. 143-157). Brill.

Ovens, A., Garbett, D., & Hutchinson, D. (2016). Becoming teacher: Exploring the transition from student to teacher. International Handbook of Teacher Education. 2, 353-378.

SFS 2010:800. Skollag [The Education Act]. [Swedish Code of Statutes]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800/

Strom, K. J., & Martin, A. D. (2017). Becoming-teacher: A rhizomatic look at first-year teaching. Springer.

Strom, K. J., & Viesca, K. M. (2021). Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. Professional development in education, 47(2-3), 209-224.

[1]For a comprehensive overview of different theoretical positions and facets on ‘the transition from student to teacher’ in research on ‘becoming a teacher’, see Ovens, Garbett, and Hutchinson (2016). The ‘becoming-teacher’ in this study is argued as a ‘both-and’ process (a WITE-student and an employed teacher), and connects to research on becoming-teacher as non-linear trajectories (e.g. Strom & Martin, 2017; Adams, 2021; Strom & Viesca, 2021).

[2]All bodies participate in the ontological memory that enables a monism of time “capable of serving as the foundation for the unfolding of time” ([1966]1988, p. 59).

[3]When deciding on a day to make the visit the only wish was if I could come on the day of their weekly practicum lesson (which was part of the WITE-agreement).

[4]On a few occasions, a becoming-teacher arrived before I did, or stayed after I had left. There were different reasons for this; a couple of times, there was a delicate parent-teacher meeting the school did not want me to sit in on. On two occasions a becoming-teacher had come in earlier than decided, and on one occasion I had to leave earlier because of the public transportation situation.

[5]More about the rules and regulations regarding the Swedish action programme, seeChapter 3, sections 8 and 9 of the Education Act (SFS, 2010:800).

[6] Visits span from the end of September to the middle of December. One becoming-teacher’s first ever practicum lesson takes place mid-December, another did not know when the first practicum lesson was to take place.