Threshold Rhythms

Mappings in this molar mosaic present the number of physical thresholds becoming-teacher crosses during one lesson and how many lessons becoming-teacher participates in during the day of the visit, together with the composition of functions during a lesson. Before we begin counting thresholds, we will take a look at Deleuzian ‘thresholds’ and also how a workday entails not only the labor of moving between spaces separated by physical thresholds, but a continuous relational calibration in connection to other ‘rhythm bodies’ involved in lesson compositions.

Milieus and Territorialization

A milieu does in fact exist by virtue of a periodic repetition, but one whose only effect is to produce a difference by which the milieu passes into another milieu. It is the difference that is rhythmic, not the repetition, which nevertheless produces it: productive repetition has nothing to do with reproductive meter. (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 314)

All bodies, I propose in Deleuzian Ontology in Education, are rhythm bodies – tessellations of speeds ad slownesses – that move through patchworks of interior and exterior milieus. The body itself is a mobile space of organ-milieus traversed by oxygen- and food-milieus – just like a garden is a patchwork of patio-, flower bed- and butterfly-milieus. Moving from one space to another thereby involves traveling across, into, and through virtual-actual thresholds. And in each crossing, the body in a split-second becomes the plaster that sutures diverse milieus and thereby becomes with the varying tempos, smells, acoustics, materials, and lights.

Upon crossing a threshold, the rhythm body acts as a converter or a mixer of different codes where “[c]oding is the process by which a thing or flow receives meaning”, Kleinherenbrink explains ([emphasis added] 2015, p. 214); ‘food’-milieu becomes human energy, and ‘patio’-milieu a place for recreation. This is another way of saying that no more than a threshold separates the comforting care offered by an assisting colleague and the nerve-wracking telephone call with an upset parent, or a busy classroom from the empty corridor. Thresholds can thus be both physical cuts into an interiority, and imperceptible passages where bodies must calibrate to one another as rhythm bodies that risk going off beat with one another.

Thresholds promise difference and demand creation. Groups of children sent into different spaces to work during class is more than a distribution of bodies in space. It is an activity that requires lesson-code turning germinal through the mobility of child-bodies when sent to work in a corridor otherwise not associated with on-task-work. This kind of code extraction where a child takes classroom assignments and continues working in a corridor, Deleuze and Guattari speak of as territorialization ([1980]1987). Code extraction is not a question of milieu-Darwinism where one milieu overcomes the other; rather, it is about creation of in-betweennesses. In the example with the lesson-milieu, in-betweenness is actualized when work elsewhere succeeds and has lesson activities transcend the physicality of classroom walls through satellite lesson-bodies. Put succinctly, it is the question of whether group work works elsewhere or not, if food becomes nutrition, if patio becomes a place to hang out. As Deleuze and Guattari propose, “In this in-between, chaos becomes rhythm, not inexorably, but it has a chance to” ([1980]1987, p. 313).

The title Threshold Rhythms, therefore, is not a suggestion that it is the repetition of threshold crossing that is rhythmic. Instead, it is ‘the in-between that has the chance to become rhythm’ as rhythm bodies with unruly tessellations of speeds and slownesses cross virtual/actual thresholds.

Thresholds are possibilities. Thresholds are imminent blockages. Stepping into a classroom, a corridor, a supply room, a staff meeting, a conversation, a school’s local intranet, or its assessment practice, involve taking a leap into the unknown. Thresholds are frontiers that can activate ostracization, alienation, adaptation, assimilation, and demand negotiation. Or offer an escape. Territorializing therefore offers the chance to create mixtures that come into rhythm;“[r]hythm is the milieus' answer to chaos”, as Deleuze and Guattari suggest (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 313). Moving between spaces is a relational labor where each threshold becomes a high-stakes game where one repeatedly must prove oneself worthy.

Sometimes you need the right key, keycard, or permission. Sometimes courage, knowledge, pass-words[1] ([1980]1987). One continuously explores what bodies are granted smooth access, which ones require authorization – may I go to the bathroom, home, into your office, away?

You have to have the password, have to cross the threshold, have to show your credentials, have to communicate, just as the prisoner communicates with the world outside. (Perec, [1974]1997, p. 37)

Each threshold is a tell sign of becoming where you must be prepared ‘to show your credentials’. Each threshold also enfolds a virtual-actual condensation of space-time(s); there is a recent past (you were here) that asks for a future (you ought to be there) through the present (you are on your way). Threshold crossing is nothing less than hard work. And for each actual threshold a becoming-teacher crosses, there are also infinite numbers of virtual thresholds encountered during a workday, where lesson compositions bring together rhythm bodies that need to calibrate to one another.

The Thresholds of a Lesson

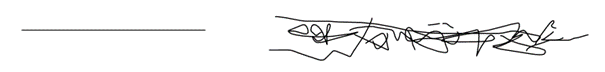

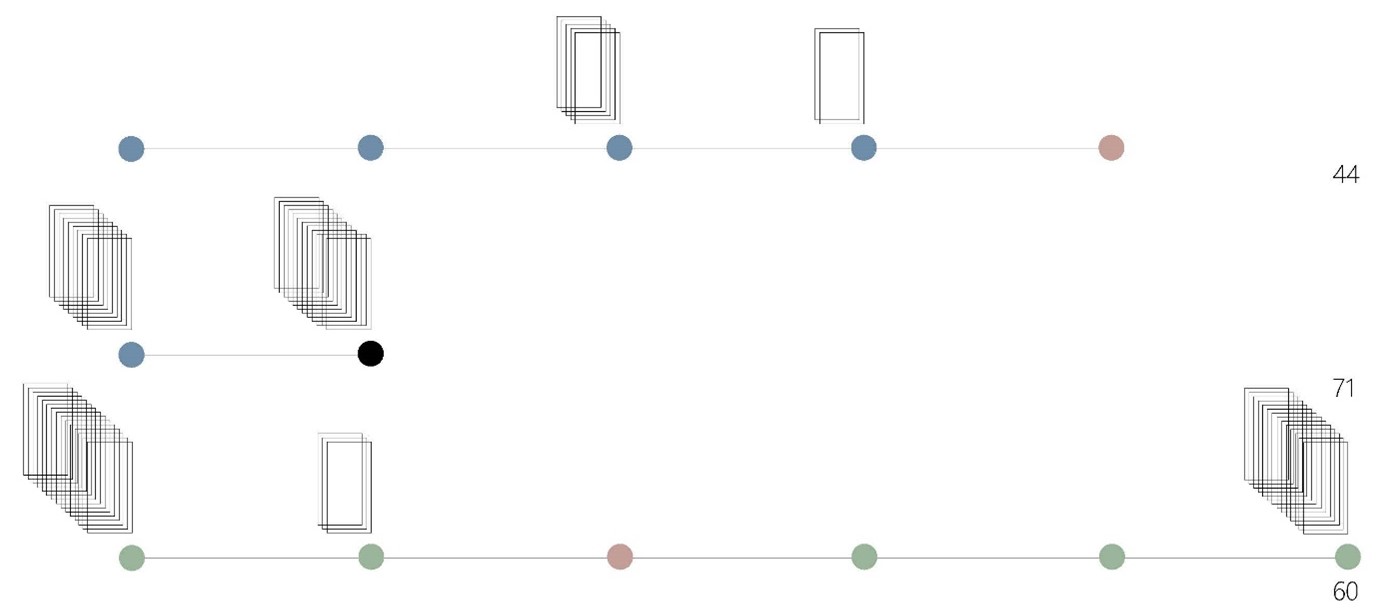

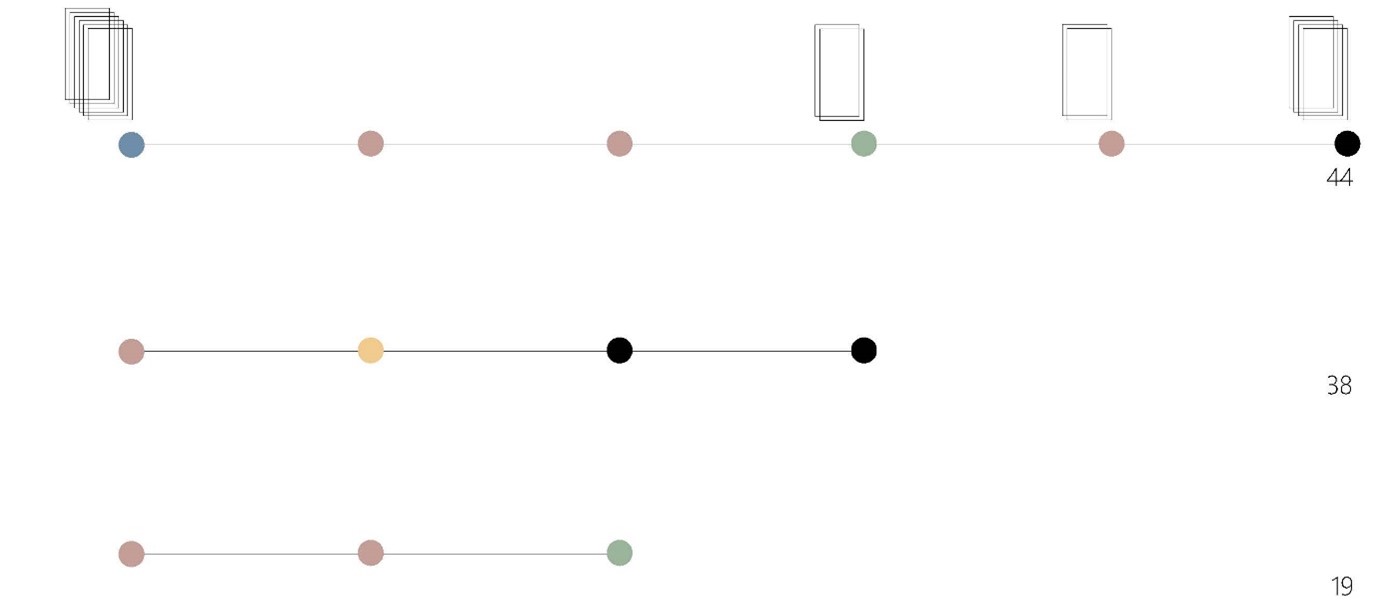

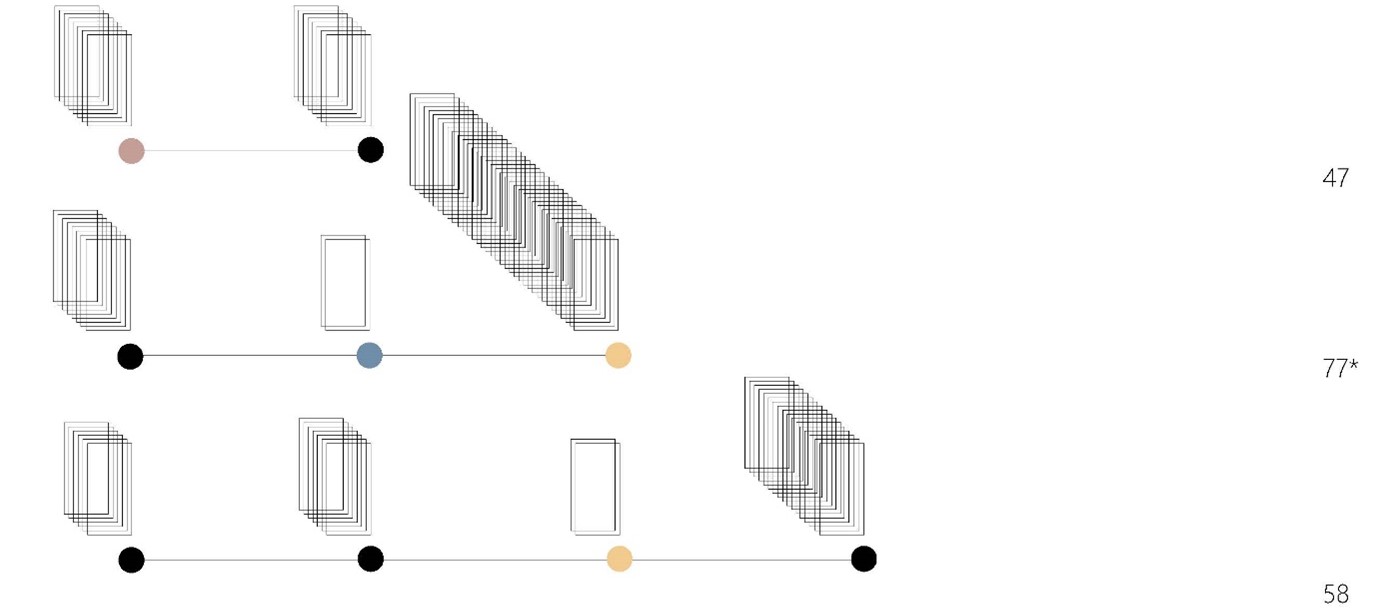

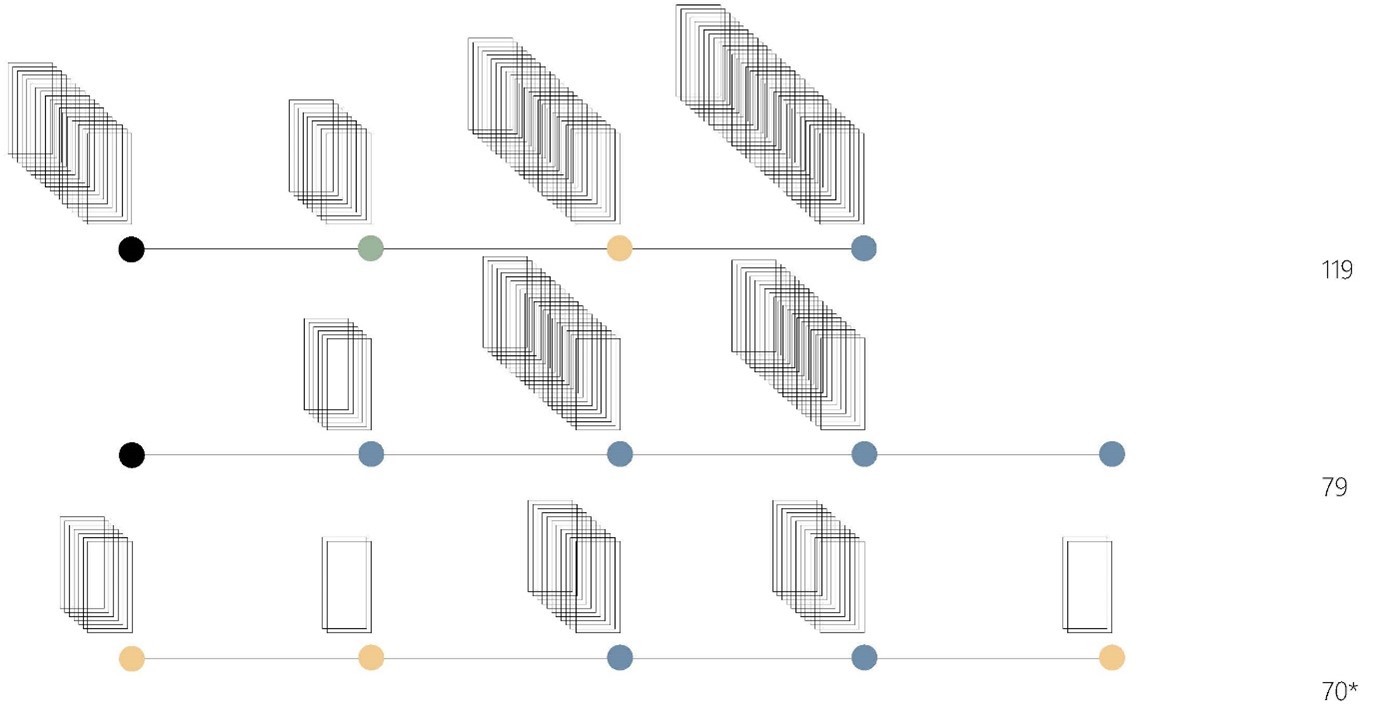

The mapping below illustrates the physical thresholds that becoming-teacher crosses during one lesson[2]. Each dot presents a lesson, and each horizontal row illustrates the number of lessons becoming-teacher participates in during the day of the visit. Numbers on the right side of each row indicate the total number of physical thresholds crossed during a workday, including thresholds outside lesson time[3].

Dots without thresholds indicate that becoming-teacher stayed inside the classroom during class. Each color offers information about the composition of adults during class. Practicum Lesson implicates becoming-teacher and a supervisor, and sometimes (a) classroom assistant(s):

Each neat line connecting lessons is to be taken as messiness looked at from afar. Were we to zoom in on the actual physical movement, the close up would look something like this:

Illustration 1: Movement Seen from afar

Illustration 2: Close

up of Movement

Thresholds

Illustration 3: Threshold Mapping

Thresholds and Spatiality

Crossing physical thresholds entails the labor of creating sense between two milieus; “[w]hat chaos and rhythm have in common is the in-between—between two milieus, rhythm-chaos or the chaosmos” Deleuze and Guattari explain ([1980]1987, p. 313). Rhythm is not about an ‘either or’ but about the in-between where the threshold is the in-between where chaos transforms.

A closer look now into the above Threshold Mapping (Illustration 3).

Staying

In twenty-two of sixty-four lessons, becoming-teachers stay in the classroom during an entire lesson. In these classes, crossing a threshold signals that class begins, and class ends, conversely, when crossing the same threshold a second time. Staying weaves a close knit between time and space that seem to augment lesson-territory – when we are here, we have class (go to mosaic Oh…). “The door breaks space in two, splits it, prevents osmosis, imposes a partition” (Perec, [1947]1997, p. 37), and when the door to the classroom closes, we leave the world outside and create a world of our own inside (The Music of (Air)plane Math).

Moving

There are other lessons when a becoming-teacher crosses thresholds ten times, twenty-four times, thirty-two times – or even thirty-six times during one lesson (go to mosaic Doorway Peekaboo). Even when the threshold seems to be the busiest part of a classroom, ‘the doing of a lesson’ can territorialize and envelop all thirty-six crossings and have them make sense as a ‘group-work’-event. Still, you may have to ‘show your credentials’ each time you cross the threshold (go to mosaics Park of Silence).

On some occasions, threshold crossing seems to act as a coping strategy, an opportunity to temporarily leave a milieu in exchange for another where one’s capacity to act can momentarily become augmented (go to mosaic The Music of (Air)plane Math).

Thresholds and Lesson Composition

Now a look at the different lesson compositions becoming-teachers enter.

Working with Qualified Teachers

Almost half of the sixty-four lessons offer becoming-teachers an opportunity to work with other teachers[4] as a partner in teaching, as an assistant to a teacher, or with other qualified teachers in the room during practicum lessons (yellow, green, and pink dots, see Illustration 3).

During partnering, becoming-teacher may be given the opportunity to take the lead and get the lesson started whilst the colleague (who can also be the supervisor) assists (go to mosaic Doorway Peekaboo); an attribute of partnership is that becoming-teacher and teacher colleague co-create a territory where both bodies are actualized, and they have equal opportunities to address the class when necessary.

When assisting, meanwhile, there is a teacher taking the lead whilst becoming-teacher needs to find an alternative function. In these setups, ‘teacher’-refrains carried out by a qualified teacher and a becoming-teacher sometimes come to mark what Deleuze and Guattari speak of as “a territory within which the same activity cannot be performed” ([1980]1987, p. 321). Becoming the ‘assistant’ then may be actualized in relation to the tasks becoming-teacher finds available in the shared space:

The supervisor

asks the class whether everybody has a ruler, and becoming-teacher begins

motioning as if looking for something. A moment later a ruler appears on the

supervisor’s desk who is still unaware of its appearance. Becoming-teacher resumes

to the back position at the back of the classroom observing with arms crossed over

the chest. The supervisor sees the rulers on the desk and turns to becoming-teacher,

and asks Have you brought out these? God, that’s great! Becoming-teacher

smiles.

…

The supervisor begins

telling the class what time it is but has no clock, I don’t know what time

it…, becoming-teacher finishes the sentence, by saying …twenty-five past

nine.

…

The supervisor is

about to show a video clip when becoming-teacher is seen pulling down the

curtains, putting out the lights, and then sitting down to watch the clip from

the back of the room next to the classroom assistant. […] The video ends and becoming-teacher

gets up and pulls away the curtains.

(E, pp. 2-7).

Still wanting to contribute, becoming-teacher needs to invent a new function; “there are [after all] rules of critical distance for competition: [this is] my stretch of sidewalk” (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 321).With ‘the teacher’-function already territorialized by the supervisor and ‘classroom assistant’ by another assistant, becoming a ‘classroom surgical assistant’ is what becoming-teacher finds available. This part entails paying close attention to what a supervisor is doing and anticipating ensuing actions before being instructed what to do. For getting instructions belongs to how ’classroom assistant’ is actualized. Despite the differences in the actualization of partnering and assisting, both still enable what Deleuze promotes as favorable circumstances for learning, namely, to ‘do with the teacher’ and being offered ‘signs to read’ ([1968]2014).

But assisting also shares attributes with the actualization of practicum lessons. Whenever a ‘practicum lesson’ entails neither pre- or post-reflections, nor opportunities to discuss the teaching with a supervisor, it is difficult to see how ‘practicum lesson’ differs from ‘assisting’ at all.

Working with Classroom Assistants

During twenty-two lessons, ten of sixteen becoming-teachers take responsibility for teaching in classrooms shared with children and classroom assistants only (blue dots, see Illustration 3). Becoming-teachers learning from other teachers is a fundamental argument for the educational design of the WITE-program. Yet, unfolding events suggest that becoming-teachers, during this first semester of the program, may come to spend much time teaching with various kinds of classroom assistants. In fact, since these different forms of ‘assistants’ have increased radically in the last five years[5], they have become common elements of today’s school ecologies (Skolverket, 2022).

There are lessons where there are two or three assistants in a classroom with less than twenty children (go to mosaic Two Hours before Fucking Whore). In today’s classrooms, there accordingly seems to be another milieu to territorialize in the many assistants that becoming-teachers need to form relations with inside classrooms. Since assistants seem to have many and varying tasks in an organization, they also come and go irrespective of when class begins. This asynchrony has threshold-crossing disrupt classroom rhythms. Existing relational compositions begin re-organizing each time a new body enters, causing arrythmia in classroom rhythm as codes from assistant-milieus need to be territorialized mid-class (se mosaic Quizzing).

Sometimes the eagerness and speed of an unknowing assistant comes to undo a becoming-teacher’s slow and patient actualization of a lesson plan:

Math class. Becoming-teacher has prepared a lesson on exponential growth and graphs where children are to work with problem solving. A classroom assistant enters.

Becoming-teacher draws a graph, and has a conversation with the children before having them try solving the problem individually, then in groups, and finally everybody together. In the joint conversation that ensues, the assistant intervenes; May I say something? Becoming-teacher has one of the children answer first, before the assistant is let into the conversation. The assistant says that what the class is working with is called ‘duplicating’ and that it is used within corporate marketing. Becoming-teacher calmly returns to the children when the assistant is finished.

Fifty-six minutes in, it is time to do the last step of the lesson plan: Becoming-teacher draws a table on the whiteboard which children help fill out. Whilst patiently taking one step at a time making sure to answer each child’s question before continuing, the assistant suddenly intervenes and says X times two, plus one, which is the answer the becoming-teacher is waiting to hear from the children. Since the assistant now has answered the question, becoming-teacher instead turns to the children to explain, So the pattern is accordingly to double and then add one. (N, p. 6)

Scrutinizing careful plans and making sure all the materials are in place, checking that laptops and projectors work, that there are markers in different colors, and cautiously taking one step at a time to make sure children follow. Not even then are there any guarantees that thresholds between rhythm bodies with divergent speeds and slownesses are crossed successfully. Someone entering is not just one more body, as the entire assemblage alters. The eagerness of the assistant enforces meter[6] that has work go off beat, despite becoming-teacher’s subtle attempts at calibrating speeds in medias res. What most likely stems from a desire to help, is nonetheless an intervention that counteractsthe pedagogical patience a becoming-teacher actualizes. Thus, more of something (like more adults in a classroom) does not automatically translate into better. Nor is assemblage quantity simply a question of numerosity. Rather, each additional body in a milieu re-organizes the entire territorial assemblage(go to mosaic Class Plasticity).

Due to the many classroom assistants, becoming-teachers not only have to plan for the ‘whats’, ‘whys’, and ‘hows’ of their own teaching and what the children are to do: they might also have to take into consideration the ‘whats’ and ‘hows’ of teacher assistants in lesson plans. Considering that lesson planning also is an area of interest for becoming-teacher, to what extent do they have access to common planning time? Ten becoming-teachers have common planning time with (a) colleague(s) on the day of the visit[7].

Working with Children

Nine becoming-teachers, or twelve lessons, involve compositions where becoming-teachers are alone in classrooms. Correction. There are twelve lessons where becoming-teachers are without other adults in the classroom; instead they calibrate themselves to between two and twenty-one child rhythm bodies.

Also, one of these nine becoming-teachers has a workday where three out of four lessons are actualized alone with children. During the fourth lesson, a teacher joins for the last twelve minutes of a seventy-five-minute class. On the day of the visit, there are few clues about how this is an actualization of ‘teacher’ in a WITE-program, other than through a comment from a colleague implying that they should not complain about workload considering that they work part-time.

References

Deleuze, G. ([1968]2014). Difference and repetition. Bloomsbury Academic.

Deleuze, G. ([1981]1988). Spinoza, practical philosophy. City Lights Books.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. ([1980]1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Kleinherenbrink, A. (2015). Territory and ritornello: Deleuze and Guattari on thinking living beings. Deleuze Studies, 9, 208-230.

Perec, G. ([1974]1997). Species of spaces and other pieces. Penguin.

SFS 2010:800. Skollag [The Education Act]. [Swedish Code of Statutes]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800/

Skolverket. (2022). Pedagogisk personal i skola och vuxenutbildning läsåret 2021/22 [Educational Staff in Schools and Adult Education for the 2021/22 School Year]. (Descriptive statistics. Dnr. 2022:276). Skolverket.

SFS 1993:100. Högskoleförordningen [The Higher Education Ordinance]. [Swedish Code of Statutes]. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/hogskoleforordning-1993100_sfs-1993-100/

[1]Deleuze and Guattari’s concept “pass-words” works together with “order-words” where the latter marks stoppages, the former meanwhile, works to unclog stoppages: “There are pass-words beneath order-words. Words that pass, words that are components of passage, whereas order-words mark stoppages or organized, stratified compositions. A single thing or word undoubtedly has this twofold nature: it is necessary to extract one from the other—to transform the compositions of order into components of passage” ([1980]1987, p. 110).

[2]Counting starts fromthe time the becoming-teacher exits the entered classroom to (an)other space(s).

[3]* = workdays where I did not participate from start to end (for details about why I did not partake an entire day, go to Memory Machines).

[4] I have not asked about anyone’s qualifications but instead registered how encounters unfold followed by a note about the definitions the becoming-teacher and/or school unit uses. Thus, someone introduced as the ‘technology teacher’, or the ‘English teacher’ I have registered in my fieldnotes as such, or just ‘teacher’.

[5]There are many different labels, and I have clustered all simply as ‘classroom assistants’. These different categories have increased radically in school settings (in schoolyear 2021/2022 there were close to 4 800 teacher assistants, which amounts to 3 500 fulltime equivalents ((in all school forms) (Skolverket, 2022, p. 22)). There are no formal education or competency requirements for teacher assistants, instead, it is the principal who decides who is deemed suitable for the job (Skolverket, 2022). Another category that also has an assisting function but haveformal education, is what in the Swedish context is called “speciallärare”, e.g. ‘special teacher’, although the few encounters with special teachers in classrooms have been categorized as ‘teacher’ in order to prevent identification.

[6]Deleuze and Guattari distinguish between ‘rhythm’ and ‘meter’, where the former entails a communication between milieus, the latter being ‘dogmatic’ ([1980]1987).

[7] And this is just one random day of a workweek which means that the remaining becoming-teachers may have common planning time on a different day.