Class Plasticity

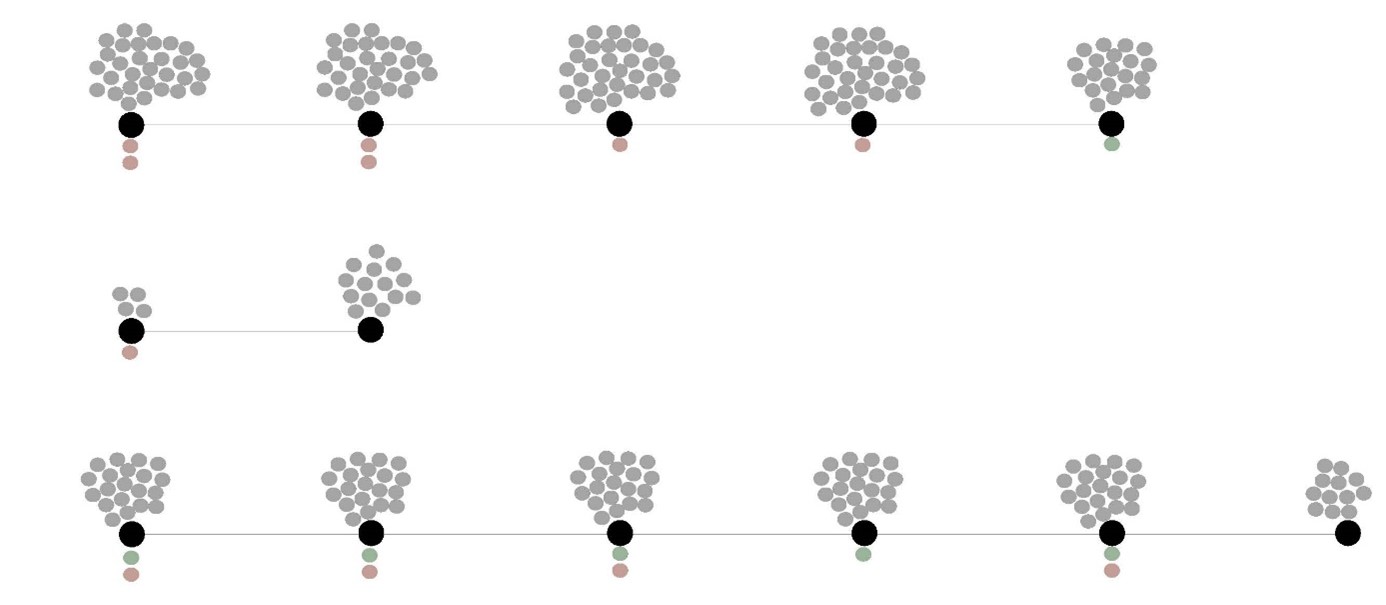

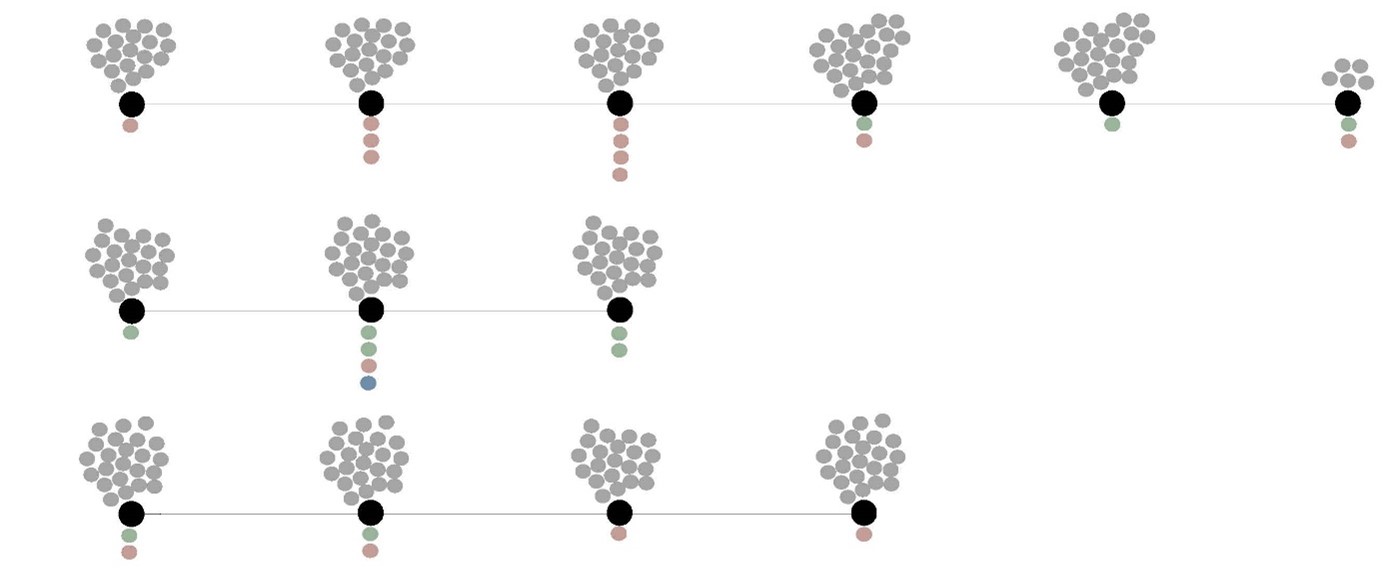

The mapping in this molar mosaic presents the total number of human bodies passing a classroom during each lesson and how many actualized functions there are present during one lesson. It also reports on the number of lessons becoming-teacher partakes in during the day of the visit.

Before said examination, we take a look at the Deleuzian ([1968]2014) understanding of the relation between ‘representation’ and ‘difference’, and in so doing demonstrate how decontextualized conversations about school events run the risk of letting important aspects of the diversity of education go under the radar.

Representation and Difference

Representation is a site of transcendental illusion. (Deleuze, [1968]2014, p. 349)

As you tell your story about what happened at work, you surrender to language. Grammar disciplines you, lexicon limits you. Sometimes the constraints of language become a challenge you decide to accept, and you create a language that enables seeing new nuances in familiar events.

Established lexical schemas filter your stories and the novelty of experiences are passed through recycled labels. Take the simple sentence: My colleague came by today, so we divided the class and had children work in groups. Familiar labels like ‘colleague’,‘child’, ‘class’, ‘group’ are part of a lexicon already loaded with meaning, masking the singularity of the event. You too participate in concept rumination and before you know it re-presentations have muddled newness:

Representational thought is ‘sedentary’, categorical and judgemental. It is the enemy of difference, movement, change and the emergence of the new. Pure difference, ‘difference in itself’ is crucified by representation. (MacLure, 2013, p. 659)

‘Representational thought’ turns organic experience into arrested images that ‘crucify difference’. But the claim is controversial and challenges the methods so much of education and professional development rest on; we represent events in seminars and meetings, write about situations in essays, reflection journals, reports, and work team minutes. Because listed activities are important. The question we might want to ask is whether there are other ways of sharing experiences.

But the tidiness of language is also convenient. How effectively the referents ‘class’ and ’group’[1] erase the messiness of a lesson’s diverse and shifting relations. Chaotic events are tidied away as the usage of readymade representations turns process into product. At best, we make distinctions by pointing at a deviance from acategory, using mathematical logics, as in ‘the class was full except for X who was at the dentist’s’ (equation: Y-1X), or by quantifying variables ‘I’ll take my group and come join your class later’ (equation: Z+Y).

We repeat shared terminology through our ‘collective assemblages of enunciation’ (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987) because it serves a purpose; it helps actualize territoriality. It manifests a ‘we’. But stagnate language may also stand in the way of sensing difference. We may even construct untouchable universals or local slogans where ‘everybody knows’ that ‘that is the talkative class’, ‘the fun group’, ‘the difficult class’. Collective truths that obscure singularity and put radical newness at stake. Or worse, collective truths have you actualize the ‘talkative’, ‘fun’, and ‘difficult’ class you have been taught to recognize. Again, language is not simply grammar, nor semantics, but a pragmatics that intervenes in the world (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987).

Sensing difference, meanwhile, is an exploration and an experimentation that representational thought seeks to resist. But neither recognition nor representation are acts of spite. Instead, they facilitate living and are even premiered processes that enable the efficient communication desired in stressful milieus. In fact, the combination recognition/representation are also taken as indictors of ‘having experience’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘being competent’.

But efficient communication also turns generic when propositions lack specificity. All is well as long as we stay within shared contexts where the vagueness of ‘class’ and ’group’ attain their meaning in the same way as the deictic expressions ‘here’ and ’there’ do. De-contextualized usage outside shared events, however, turn referents into empty signifiers – or have signifiers semantically hijacked by competing contextual understandings. Whether ‘my class’ refers to someone explaining how they instruct six children to work in groups, or twenty-six children work in groups, will make a difference that at times risks going under the radar.

Sharing and problematizing experiences from work and practicum during discussions are thus established practices used in formal education, staff meetings, and child-parent conferences. During such discussions, the use of common referents such as ‘class’ or ‘group’ therefore illustrate how quantitative specificity can be a qualitative facet of school events. The ensuing mapping therefore examines the quantitative plasticity of the representation ‘class’/‘group’ as referent of actualized lessons in a WITE-program.

A Class

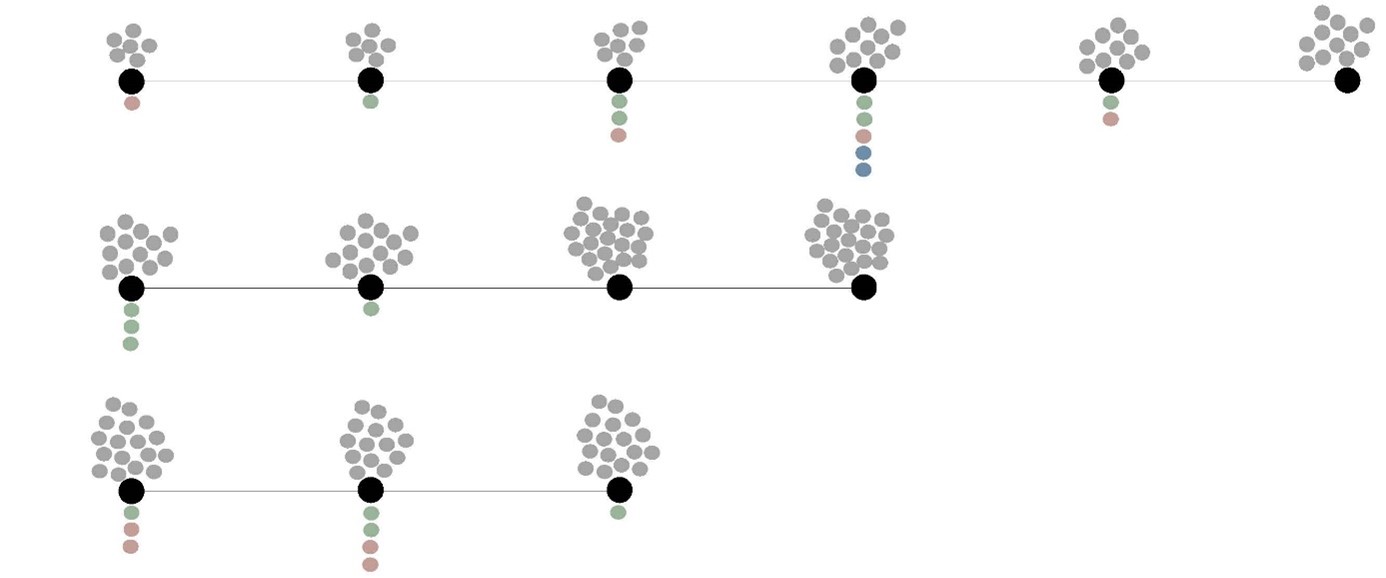

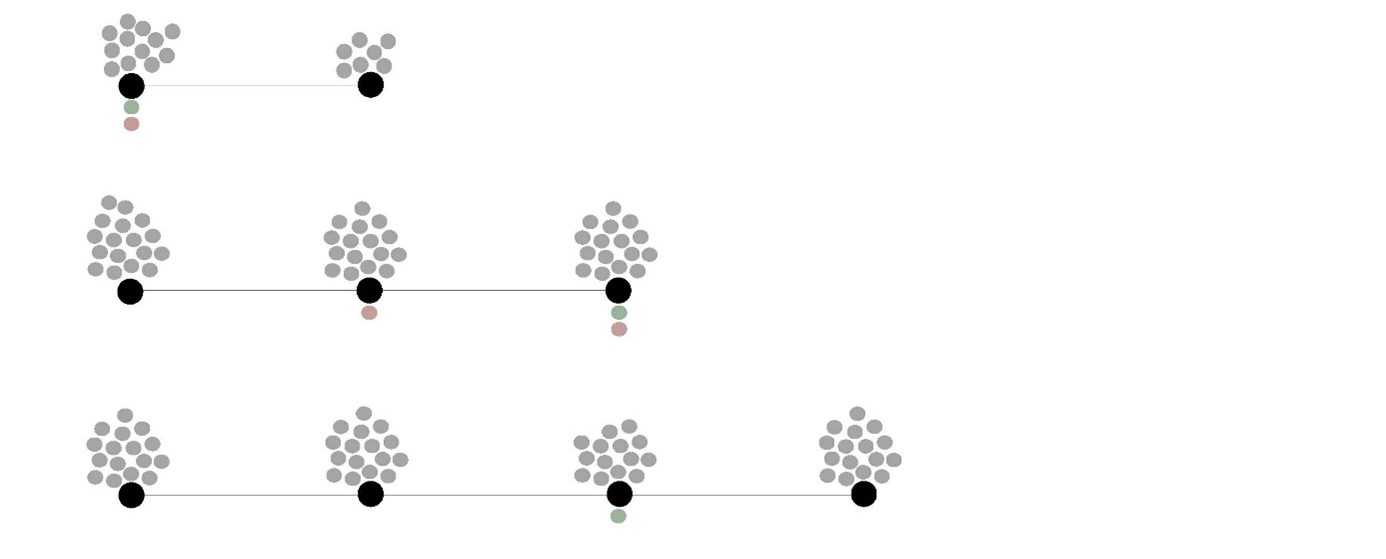

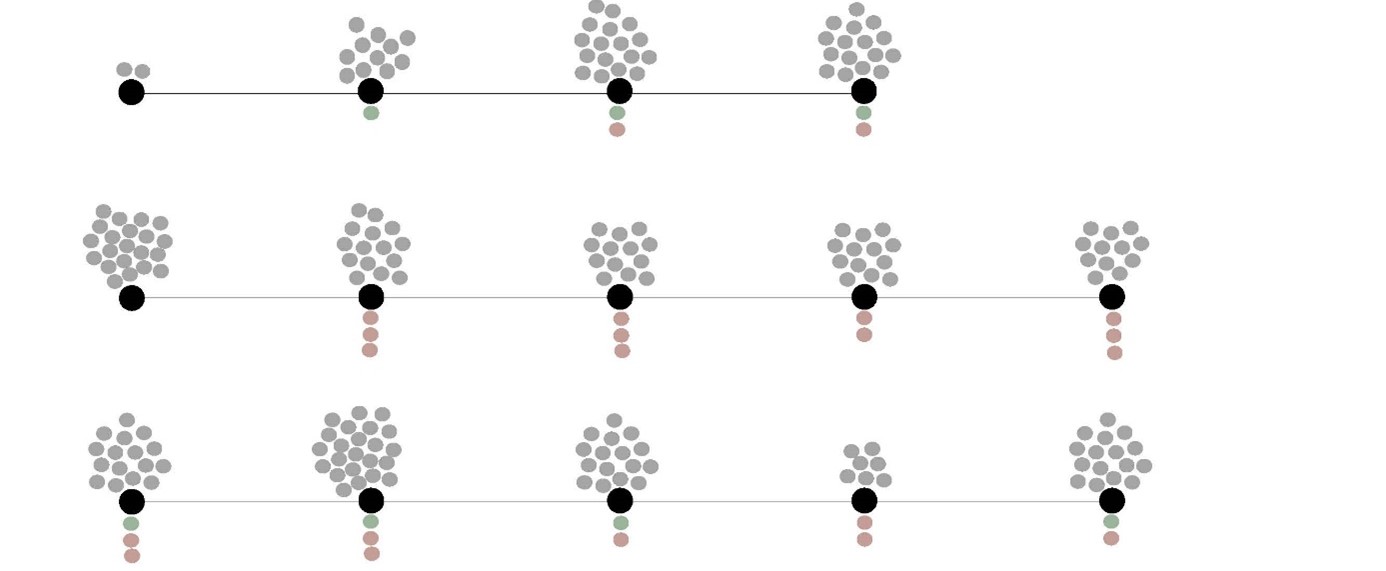

The mapping shows the total number of human bodies passing a classroom during each lesson. Each cluster also indicates how many actualized functions there are present during one lesson. Dots indicate bodies’ actualized functions in the shared space-time (add one dot to each cluster and you have my body also in mapped quantities).

Each row also shows the number of lessons becoming-teacher partakes in during the day of the visit, so five clusters in a row indicate there are five lessons during the day of the visit.

Each neat line connecting lessons is to be taken as messiness looked at from afar. Were we to zoom in on the actual physical movements, the close up would look something like this:

Illustration 1: Movement seen from afar Illustration 2: Close up of Movement

Class

Illustration 3: Mapping of Human Bodies in a Class

The Quantities of Class

Actualizations suggest that the representation ‘class’ is a diverse and changing word when used as a quantifier; there are differences both between different classes over the course of a becoming-teacher’s workday, and differences between different becoming-teachers (and over the course of a lesson, as the concluding section will discuss).

The Difference is Twenty-Eight

Four is the smallest number of children referred to as a class (go to mosaic The Music of (Air)plane-Math), thirty-two the largest (go to mosaic Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock).

One becoming-teacher moves between classes that encompass six but no more than eleven children over the course of a day (go to mosaic Following John), while someone else shifts between a group of nineteen up to twenty-three children (go to mosaics The Backwards Booklet, Oh… and Blank Maps). A third becoming-teacher consistently has large groups where three out of five lessons have thirty children or more.

Two clusters in the above mapping are not discussed as a ‘class’: The first is a session with two children seated in two different spaces. The second is a ‘homework assistance’ session. The former is articulated as ‘one-to-one work’ where becoming-teacher assists one child (even though becoming-teacher on the day of the visit needs to take a second child due to a colleague having called in sick). The other gathering not discussed as a ‘class’ (instead referred to as a ‘group’), is a non-compulsory session children can go to if they want help with their homework. On the day of the visit, the homework session gathers five children.

Child-Adult Ratios

The section Threshold Rhythms discusses the composition of adults in connection to what extent becoming-teacher is offered opportunities to ‘learn with’ qualified teachers, classroom assistants, and children. The clusters in this mapping, meanwhile, show the ratio between children and adults.

The perhaps most notable ratio is mapped in a lesson with ten children to six adults (with me included, seven adults). But the number of adults must not be mistaken as an indicator for access to help. In a crammed space intended for group work, a temporary remodeling has a class of ten moved into this small space where a becoming-teacher is to assist a colleague during math. However, on the day of monitoring, the school has politicians visiting which is why an already too small space with too many bodies is accompanied by three more adults (two from outside the organization and another teacher colleague). They are all there to observe the class as part of their visit. As the principal makes a brief stop to oversee the visit, there are six adults and me observing ten children. The situation is bizarre.

In another lesson, the child-adult ratio is nineteen to five, suggesting children have ample opportunities to one-to-one time with an adult. However, on closer inspection the dot-cluster can be seen to be an effect of a visit from two colleagues coming to speak with a group of children before leaving.

In a third lesson, the visit from a dental nurse adds one dot to a cluster making the one-minute presence leave a dot-scar of the same magnitude as someone staying. Thus, the side-effect of looking at quantity is that the above mapping hides the temporal sides of a lesson and thus the fluctuations in quantity. Durations are collapsed into instants that swallow change which is why quantity becomes an arbitrary estimate of multifaceted activities. ‘Lesson’, similarly, is a noun that hides an implicit time interval with a chronologically fixed start and end time. The word ‘lesson’, therefore,is what in Deleuzian Ontology in Education is proposed as a semachron – a ‘sign of time’.

But there is also another effect, where turning process into product and continuity into ‘class’, form a map that enables posing new questions. In a space with fourteen children, collapsing time makes it apparent how five adults come and go during one lesson. Since these adults never stayed in the classroom at the same time, their many-ness went undetected. A new question to ask about lesson as event is: how does the coming and going of adults during class affect the assemblage? (for a problematization of the impact of change in assemblage composition, go to Threshold Rhythms). Consequently, looking at ‘lesson as process’ adds significant dimensions to an understanding of ‘lesson as product’, and new facets of school life come into view that add to the mapping of teacher- becoming.

Child-adult ratios are accordingly not automatically given measures for estimates on whether children, or becoming-teachers for that matter, can get more help during class. This is not to say that more adults per child is not beneficial; rather, it becomes important to examine what these adults do, and how collaboration between school staff is organized.

In one assemblage, a becoming-teacher attains assistance from two or three classroom assistants over the course of four lessons. This generates a child-adult ratio of between twelve to fifteen children, to three to four adults. In what unfolds as volatile and intense events (go to mosaic Two Hours before Fucking Whore), this becoming-teacher is monitored trying to manage escalating situations whilst partaking adults stand by observing. All adults in the room seem incapable of mobilizing necessary resources to help becoming-teacher and children ‘compose relations’ in more constructive ways. Or is actualized passiveness an effect of their division of labor? Or is passiveness the effect of a lack of a division of labor? Or is this what involved adults think a lesson should look like?

Either way, if becoming-teacher is to learn by observing how other adults in school handle the unfolding situation, then becoming-teacher learns that one can leave chaos by taking a child and going. More adults, therefore, may not solve the problems of education.

Quantity as Quality

As the mapping Threshold Rhythms proposes, each actual-virtual threshold a body crosses requires work to extract code from involved milieus to create a territory. This is to say that each dot in the above clusters is a potential ‘class’-modulator whose movements have the capacity to create qualitative difference in a ‘class’ or ‘group’ (more about differences in degree and kind, go to Deleuzian Ontology in Education). Assistants coming and going affect lessons.

That there are ‘too few’ teachers, is a politically charged observation that includes questions about class size and child-teacher ratios. And the way many Swedish schools have come to solve this question is by hiring various types of ‘assistants’, primarily adults without teacher qualifications (Skolverket, 2022). However, a question that statistics from school organizers fail to report, just like the above mapping fails to illustrate, is how classroom assistants affect an educational space. To see how they seem to affect teacher becoming, go to mosaics Quizzing, Two Hours before Fucking Whore, The Music of (Air)Plan-Math and When Outside Becomes Inside.

Accordingly, even when quantities are correctly presented, this does not make them true. Put differently, anomalies and fluctuations over time hide amidst the neatness of numbers and linguistic categories, which is why we must make sure to ask how cuts are made into the reality that numbers and language seek to represent. This mapping indicates that ‘class’ and ‘group’ ought to be taken as plastic representations when used as indefinite quantifiers in decontextualized situations. Said another way, to report the rich texture of experience through language in de-contextualized situations, representations such as ‘class’ and ‘group’ demand quantitative detailing together with processual information, to resist turning process to generic product. For there is no such thing as re-presentation; sharing stories might instead be used as sites of becoming.

References

Deleuze, G. ([1966]1988). Bergsonism. Zone.

Deleuze, G. ([1968]2014). Difference and repetition. Bloomsbury Academic.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. ([1980]1987). A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

MacLure, M. (2013). Researching without representation? Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology. International journal of qualitative studies in education, 26(6), 658-667.

Skolverket. (2022). Pedagogisk personal i skola och vuxenutbildning läsåret 2021/22 [Educational Staff in Schools and Adult Education for the 2021/22 School Year]. (Descriptive statistics. Dnr. 2022:276). Skolverket.

[1]Class and group are used in a similar manner as the context dependent deictic expressions ‘here’ and ‘there’. The term ‘group’ is used in two slightly different manners; sometimes it is used synonymously with ‘class’, on other occasions the word ‘group’ comes to serve as a tool of division where ‘a class’ is divided into smaller ‘groups’.