Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock…

It looks me gravely in the eyes and decides: You have one minute. In that one minute you have to run around the equator on foot. When one minute has passed, you have to be back again – if you want to live, that is. It turns silent, looks at me to make sure I have understood the task, and then nods to let me know there will be no more instruction. With the point of a finger, I am guided to a line drawn in the gravel. On your mark, get set… go! 60, 59, 58, 57, 56…

This has been a returning nightmare for more than thirty years. Each time I arrive at the part where the countdown begins, panic builds. What terrifies is the absurdity of the task. What world is at play where creatures are assumed to have the capacity to run at the speed of light? Perhaps this is where the profound terror resides; not knowing whether ‘it’ and I are alien to one another. Do we share any worldly points of reference? And if not, what are the prospects of communicating the absurdity of the task in the few seconds available before the task is to be executed? So, what to do when one’s Weltanschauung[1] is at stake? Dig your feet deep into the gravel, get set – run!

Let us now move to the event that made this old nightmare come to mind. There is something about the way universal principles become suspended in the observed corridor sprint that causes a sense of unease. Although there may be no instructions to run around the world, there is nevertheless a nonhuman body instructing a becoming-teacher to do the impossible. And because of the instruction, a becoming-teacher is trying to compete against time in a way that is uncannily similar to the scene in the nightmare. Let us move to the event.

Did Not Go Very Well…

The becoming-teacher we are about to join has just returned to the study from two consecutive Swedish lessons with fifty-nine children in total. In just four minutes’ time, becoming-teacher will greet thirty-two new children and do another hour of Swedish. But first a quick pit stop at the shared office.

9.36, the office.

Becoming-teacher takes a sip of cold coffee from this morning’s coffee cup.

Stands by the desk, turns to the colleague, and says It

did not go very well with the X and Y graders.

(B, p. 6)

What could have happened to have becoming-teacher conclude that things ‘did not go very well’? Arguably, a million and one things could, and did, happen. With nowhere better to enter, let us follow Deleuze and Guattari’s proposition ([1980]1987) and simply step straight into the middle of events. As we move into the classroom and an ongoing quiz, becoming-teacher has two minutes before next class begins.

Running

8.48, becoming-teacher is finishing the quiz; two

minutes before the next class begins.

Thirty children who are still leaping in a

question-and-answer mode.

A child thinks out loud, They are

violating human rights...

Becoming-teacher says, We don’t have

time for any more rights now. All X graders, you’ll have to listen, look at me.

I’ll wait until all eyes are on me. (B, p. 3).

The children are thinking and engaging with the quiz, while becoming-teacher is thinking and engaging with the schedule. The schedule offers no time for human rights. When yet another child raises a hand to make a comment, becoming-teacher declares that there is no more time for questions. The activity is aborted, and with no activity that assembles the class, the children begin exploring alternative things to do. Becoming-teacher has much to finish and little time to do so. A dual movement of finishing-preparing ensues. Tick-tock, tick-tock…

The clock says 8.53. Three minutes past lesson time, three minutes late for next class. Becoming-teacher hurries to materially recompose the room that needs leaving. Turns off the projector. Takes the cart with materials. Locks the classroom.

Four minutes since Swedish lesson one ended, four minutes late to lesson number two. Becoming-teacher runs to physically compensate for the now five minutes becoming-teacher is late to lesson two. Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock…

8.55, becoming-teacher enters the

classroom. Continues to the corridor. Fetches the twenty-nine children waiting

in the corridor.

Invites the children into the classroom, Please,

go ahead. 8.58, back inside the classroom.

Becoming-teacher goes to wait in the front

of the classroom, and a classroom assistant enters. An attendance sheet is visible

on the whiteboard. Becoming-teacher clarifies, Now, everybody needs to quiet

down so that I can hear that everybody is here.

Becoming-teacher informs the class that

the coworker is home sick. Becoming-teacher talks about the upcoming quiz,

looks for a pen – a child points at the pen.

Becoming-teacher talks about how becoming-teacher

wants the class to behave during quizzing. Are we being assessed? a child

asks. Becoming-teacher says, No.

Becoming-teacher reads a question, I´m

reading, the becoming-teacher says to a child, I asked you to be quiet. (B, p. 4)

Eight minutes since Swedish lesson one ended, and eight minutes late becoming-teacher and twenty-nine children finally arrive inside the classroom to get started. Almost a fourth of the lesson is now gone and attendance checking, that in the first lesson was an opportunity to engage with the children, here becomes a staccato task best made away with quickly – preferably in silence.

We are here closing in on one of many answers to the question of ‘how encounters unfold and with what effects’. A becoming-teacher running through a corridor to band-aid dislocated lessons is a symptom of a phenomenon we must take a closer look at. Perspiration and shortness of breath now form a bridge between Swedish lesson one and Swedish lesson two. But do lessons need corporeal band-aiding, or could it be that the experienced dislocation is an effect of something else?

The investigation of what is going on in monitored assemblage cannot rely on reductionist categorical thinking through ‘identities’, meaning autonomous, pre-definable and stable entities. We are not helped by asking what components the assemblage comprises.

[I]t is not sufficient to simply enumerate an assemblage’s material components because these do not by themselves disclose the assemblage’s constitution, much less its purpose or function. One must also ask how these material components are captured by the expressive dimension and inquire too about its principle of unity and its conditions of possibility. (Buchanan, 2021, p. 122)

This assemblage has many, if not most, components in common with other school assemblages (children, lessons, materials, corridors, schedules), yet running does not automatically ensue from these circumstances; so, to ‘simply enumerate an assemblage’s material components’ add nothing. “The assemblage is intended to answer several types of question, ‘how?’, ‘why?’, ‘when?’ and not just a ‘what?’ question” (Buchanan, 2021, p. 13); so we need to explore the more critical question, why is this happening?

Buchanan’s reading of the Deleuzoguattarian project and assemblage theory[2] argues for the need to examine the ‘formal structure’ of assemblages, precisely for the above reason and since assemblages “are not necessarily arranged in the same way” ([my emphasis], Buchanan, 2021, p. 79). This mosaic examines becoming-teacher running as an actualization of a schedule. I therefore need to take a closer look at the relation between running, schedule, and school organization and layout.

Institutional Weltanschauung

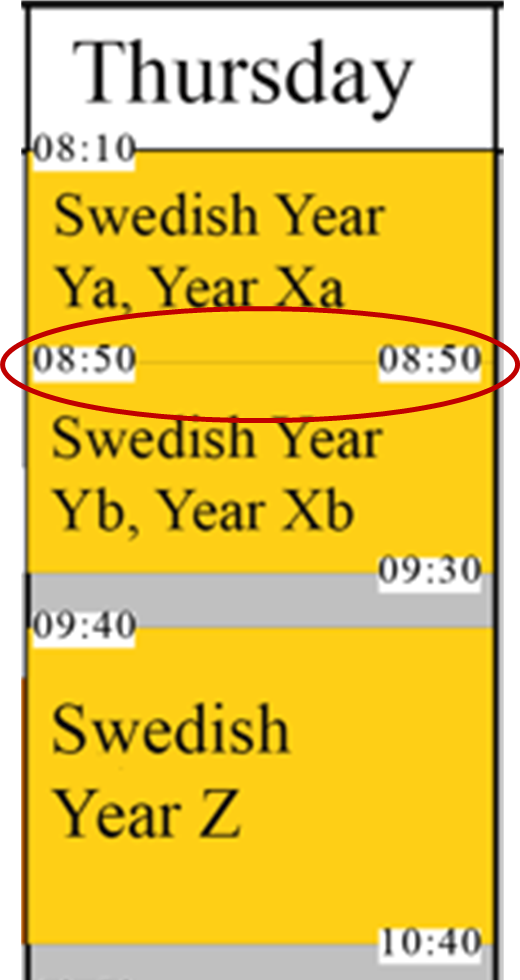

Illustration 1: The Schedule

The red circle in Illustration 1 indicates the thin brown line that participates in the making of what becomes the 'It did not go very well'-comment. Although schedules have neither deterministic power nor correspondence to reality, they do have 'the capacity to affect and become affected' (Deleuze, [1981]1988). A thin brown line in a schedule can make a raw cut not only into a Swedish lesson, but into the flesh of a body. Pixels move beyond the screen and onto the chemistry of a body where inscription continues through cortisol increase, pulse elevation, and sweating.

Admitting that the schedule intervenes in life explains how scheduling sketches an institutional Weltanschauung. A thin brown line becomes the expression of an institutional assemblage, meaning 'a school assemblage's construction of the relation between time, space, activity and body-relations, told through letters, numbers, and geometry' - a kind of molding of a worldview proposed possible to its recipicents through the schedule. This is where schedules become an 'ethico-political' question. I will return to this shortly.

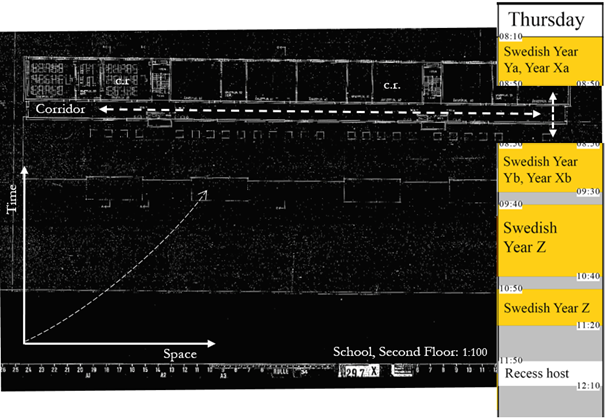

Blueprints

Illustration 2 below shows becoming-teacher’s schedule and the school’s spatial layout. The figure illustrates that there is a critical point where the actual ‘physical distance’ between rooms that the BT needs to move between when shifting from Swedish lesson one to Swedish lesson two, begin to act as a lever prizing apart – increasing – ‘time as distance’, in other words, the way time is visualized in the schedule.

Figure

2: Expanding dislocation between ‘schedule as visualization of time as

distance’, and ‘blueprint as visualization of physical distance’ as

effects of actualized running

The schedule affects the running-body but running through corridors also affects the schedule. Said differently, the schedule’s relation to the reality it seeks to represent changes each minute spent running.

Could one of many answers to the question ‘why’ this is happening be (where ‘this’ refers to the absence of time between lessons in an institutionally sanctioned schedule), through the way in which lesson-rectangles mimic the visual language of blueprints. A space transposed from a building to a blueprint remains within the same system of measurement (‘physical distance’). Schedule’s ‘time as distance’, on the other hand, has no correspondence whatsoever to spatial conditions and ‘physical distance’. Quite the opposite, Figure 2 shows. The physical distance in the corridor where becoming-teacher is running has a peculiar yet visually counterintuitive covariation with time as distance: it seems that the smaller the distance between rectangles in schedules (time as distance), the greater is its impact on physical distance. The banality of this proposition becomes obvious when separated from the schedule context, outside ‘Institutional Weltanschauung’: Running through a corridor requires more time than staying put in the same space. As simple as that.

Tetris

Time told as distance through geometrical figures enables aligning rectangles in neat columns. Forty minutes of Swedish through Tetris-logics begs another rectangle be placed nearby, preferably back-to-back to the first one. The ingenuity of both numbers and squares is also that no matter how closely they are placed, they still manage to remain discrete entities. Messy reality, conversely, leaks everywhere. Another possible answer to ‘why’ this is happening could be because Euclidean logics implores neatly stacked columns. The triviality of the proposition becomes apparent when removed from the schedule context, outside ‘Institutional Weltanschauung: A schedule with ordered columns and geometric figures is more accessible and easier to display on small screens.

With that said, there is nothing banal nor trivial in the effects of this institutional lapse. Instead, paradoxical institutional Weltanschauung in schedule stories appear to be a well-known theme in the school context. Unions even offer advice on questions regarding worktime and schedules:

During the working day, enough time is needed between lessons so that you have time to tidy up the classroom, let students in and out, and move if you are going to another room.

- Of course, you should not have to run between the classrooms, as you must have time to breathe, drink water or perhaps document something. It is very important to have small breathing breaks during the day, so the schedule must not be too compact.

Even if you are still in the same classroom with the same pupils but have to change subjects, time is needed between lessons.

- I have seen schedules where primary and middle school teachers have a math lesson that ends at 13:00 and then a Swedish lesson that starts at 13:00. It does not work in practice. Lessons need to be at least 10 minutes apart, preferably more. Otherwise, you will lose a lot of lesson time.

([my translation], lr.se[3])

Becoming Rational

But even in the light of alluring linearity there does not have to be a thin brown line, and even if there is one, it does not have to be translated into running.

Asking what constitutes a schedule in “a material-semiotic sense, […] corresponds to the internal limit of the assemblage” (Buchanan, 2021, p. 130). Localizing these internal limits can help question how these particular lines came to be. In other words, the inquiry becomes a scrutiny of the construction of the points of reference used in this ‘institutional Weltanschauung’:

[M]aterial isn’t, on this view of things, merely a condition of possibility […]; rather, it is anything which can be interpolated and accommodated by the expressive sphere. Material must always be produced; it doesn’t simply exist. […] We have to resist the empiricist tendency to treat material as given and instead ask the more properly transcendental-empiricist question: How and under what conditions does matter become material? (Buchanan, 2021, p. 131)

The ‘matter’ of the thin brown line becomes schedule ‘material’ when a school organization knows they are short-staffed. There was “supposed to be six teachers and ninety pupils, but at the moment there’s only three and a half – two more are expected to come later this year” (B, p. 10).

Schedules tailored to accommodate the requirements of the national time plan[4] may have pushed aside the needs of teachers and their working conditions as an effect of actual staffing conditions. But even if there is an accurate distribution of hours listed in a schedule to ensure children that attain the hours of teaching they are entitled to, the group of children in Swedish lesson two might still be at risk if the schedule becomes difficult (impossible even) to actualize due to organizational circumstances and spatial conditions.

Too few qualified teachers in the system opens to creative, but precarious solutions to organizational issues. The school unit may choose to actualize a becoming-teacher as equivalent to a ‘qualified teacher’. Being designated as ‘qualified’ might potentially empower becoming-teacher and give opportunities to perform a broader repertoire of tasks, but it also gives the employer leeway to assign more tasks but less time working together with other qualified teachers.

Being short- staffed also forces the school-assemblage to ‘use’ what teachers there are ‘wisely’. In this case, there is the additional complexity of having a becoming-teacher on staff where two workdays in a becoming-teacher’s schedule are already claimed due to necessary synchronization with the WITE-program. In other words, organizational conditions entangle with the confusion of the distance seen in blueprints and the allure of Tetris-logics and snug rectangle stacking.

Schedules connect to multiple processes and trying to actualize the schedule proves the openness of reality. During the day of the visit, becoming-teacher is greeted with the words “Two sick” (B, p. 1) less than thirty minutes before classes start, and suddenly becoming-teacher’s day changes. ‘Two sick’ thus becomes yet another condition whereby the ‘matter’ of a thin brown line becomes a very specific schedule ‘material’. And when becoming-teacher replies “I’ll solve that” (B, p. 1) it changes again. There is an intensity of ‘Two sick’ that conjugates with the schedule’s thin brown line, with the effect that colleagues through collective efforts solve what the school-assemblage fails to solve. And the fact that it is the supervisor who delivers the two words becomes yet another condition for what becomes.

As colleagues now begin counting on-site personnel, they conclude that there are no more than two full-time teachers and one part-time teacher to take care of ninety children – one of whom is a physical education teacher allocated primarily to the neighboring building. With becoming-teacher’s co-worker sick, becoming-teacher is the only teacher who can actualize a thin brown line constructed on the premise that there will be two human bodies to uphold it. And this, like in the nightmare, is yet another of many possible answers to the question ‘why is this happening’ – because there are only seconds to find a solution to a problem that, in thinking with Deleuze’s Bergsonian notion of duration ([1966]1988), could be stated differently to begin with – had the teachers been the ones articulating the problem.

Messy relations and seemingly insignificant decisions affect becoming-teacher’s workday. And yet in each decision where the schedule is maintained apt through the school-assemblage, ‘apt’ becomes “an ethico-political judgement about what kinds of houses [here: schedules] people ‘ought’ to live in [here: navigate by]” (Buchanan, 2021, p. 132). This is a question connected to the schedule’s external limits, its “ethico-political sense” (Buchanan, 2021, p. 130-1[5]) – or in my words, the ‘institutional Weltanschuung’. And here, running through corridors to physically band-aid dislocated lessons has become a completely rational way to uphold schedules.

The Making of ‘Did not go very well’

Becoming-teacher in the ‘it did not go very well’-comment speaks of carried-out lessons. Classroom activities in this articulation disregards organizational conditions. Schedule-affect and having taken care of fifty-nine children only to take on thirty-two more in just a few minutes are forgotten circumstances. Complex processes are understood reductively as lesson outcome, entangled reality, individual responsibility. Schedule-affect thereby unnoticeably nestles its way into the heart of classroom activities and self-perception.

“We must, however, distinguish between the actions and passions affecting those bodies, and acts, which are only noncorporeal attributes or the “expressed” of a statement” Deleuze and Guattari stress ([1980]1987, p. 80). The “incorporeal transformations” they speak of ([italics in original] Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 80) should not, however, be understood as less intense or less real. Instead, non-corporeal attributes become as real as the sweat on becoming-teacher’s shirt. It is through incorporeal transformation that schedule-affect makes becoming-teacher ‘late teacher’, and the second lesson the ‘delayed Swedish lesson’. The use and effect of noncorporeal attributes also have the capacity to intervene materially; one need only think about what is granted or restricted through ‘diagnosis of children’, ‘assessments in education’, and the use of ‘evaluations as grounds for qualification’ to further studies – all examples of noncorporeal attributes that generate incorporeal transformations. Effects of attributes materialize as they constrain or give access to resources by deciding who ‘passes’, who ‘fails’ and affects material (living) conditions.

A thin brown line goes, if not undetected, at least unquestioned even though it suggests a creature capable of running at the speed of light, cloning, or that there at least be warp zones. But in the absence of super-human capacities, and only seconds to find a solution, a becoming-teacher gets ready and runs. And if the schedule becomes the metric of evaluation, becoming-teacher fails.

Seemingly passive pixels on a screen, or ink on paper, have now managed to elevate human pulse, cause sweating, and have made feet run, thereby producing sound through corridor-ruckus-making. Not least they have decreased children’s lesson time. And have made twenty-nine children wait outside a classroom door. Schedule-affect thus participates in Swedish subject-becoming, and in teacher- becoming.

So, one of many answers to the posed question ‘what affects becoming-teachers during a workday’ must therefore be: A thin brown line. Why thin brown line-affect works the way it does can be traced in innumerous directions, some of which have been sketched in the above sections, such as the collegial desire to solve impossible schedules caused by lengthy staffing shortage. Tick-tock, tick-tock…

References

Boeskens, L. & Nusche, D. (2021). "Not enough hours in the day: Policies that shape teachers’ use of time". OECD Education Working Papers, No. 245. OECD Publishing.

Buchanan, I. (2021). Assemblage theory and method: An introduction and guide. Bloomsbury Academic.

Bäckström, P. (2021). Psykisk påfrestning och samvetsstress i lärares arbetsliv. Arbetsmarknad & Arbetsliv, 27(3), 27–44.

Deleuze, G. ([1966]1988). Bergsonism. Zone.

Deleuze, G. ([1981]1988). Spinoza, practical philosophy. City Lights Books.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. ([1980]1987). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (Massumi, B., Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[1]Weltanschauung: a comprehensive conception or apprehension of the world especially from a specific standpoint : WORLDVIEW (n.d., merriam-webster.com)

[2]Buchanan offers the Deleuzoguattarian project as ‘assemblage theory and method, “an incomplete project that invites us to develop it further on the basis of a few ‘first principles’” ([italics in original], p. 6, 2021). The venture is a critique against thinkers such as DeLanda´s ‘assemblage theory 2.0’, and various other ‘New Materialists’ such as Jane Bennett and ‘vital materialism’; the latter is an approach that attains one of the harshest blows in Buchanan’s return to the proposed ‘first principles’ (Buchanan, 2021, p. 113ff.). The counter term that Buchanan proposes based on Deleuze and Guattari’s thinking and oeuvre, is ‘expressive materialism’ (2021).

[3]Interview with the principal safety representative ‘Lärarnas Riksförbund Stockholm’, a union article on questions about scheduling. Lärarnas Riksförbund. (n.d.). 7 schemafrågor att hålla koll på: Huvudskyddsombudet: Så granskar du ditt schema. Retrieved 30 June 2022, from: https://www.lr.se/lon-lagar--avtal/arbetstid/7-schemafragor-att-halla-koll-pa

[4]Children in compulsory school are entitled to a minimum number of guaranteed teaching hours. The timetable describes how the teaching hours are to be distributed between the different subjects. At the time of this inquiry, the time plan is specified per stage (4-6). It is the principal who decides the distribution of teaching hours per grade.

[5]This line of reasoning resonates with Buchanan’s discussions about the ‘house’ as an assemblage (2021). The house-example references a project by Tess Lea (e.g. Lea, 2014; Lea, & Pholeros, 2010, cited in Buchanan, 2021) about indigenous housing policy. Buchanan then through the lens of Lea’s ‘house’ as an assemblage discusses how the materiality of the house is used to “raise questions in the expressive sphere” (Buchanan, 2021, p. 122). [Lea, T. (2014). “From little things, big things grow”: the unfurling of wild policy. E‐flux, 58, 1-8. ; Lea, T., & Pholeros, P. (2010). This is not a pipe: The treacheries of indigenous housing. Public Culture, 22(1), 187-209.]