Themes on a Silence

Forty-three minutes of an art class with twelve pupils in a classroom and two more sitting outside working. This mosaic offers two themes on a silence from within an art class. Said silence is elsewhere discussed as a ‘voicelessness’, here visualized in two introductory illustrations (Illustration 1, Illustration 2). Following the presentation of the two themes, I discuss the notion of representation and its relation to sound. Lastly, an inquiry into each theme where the challenges of writing sound are explored. This mosaic therefore not only asks questions about encounters and their effects, but also about ‘what affects the reports of said effects’. Why, you ask. Because it may be that established research practices put at stake what stories can be told.

Theme I

Illustration 1: Wordless Voicelessness

Theme II

Coloring-Pencil-on-Paper Dropping-Keys-on-Table

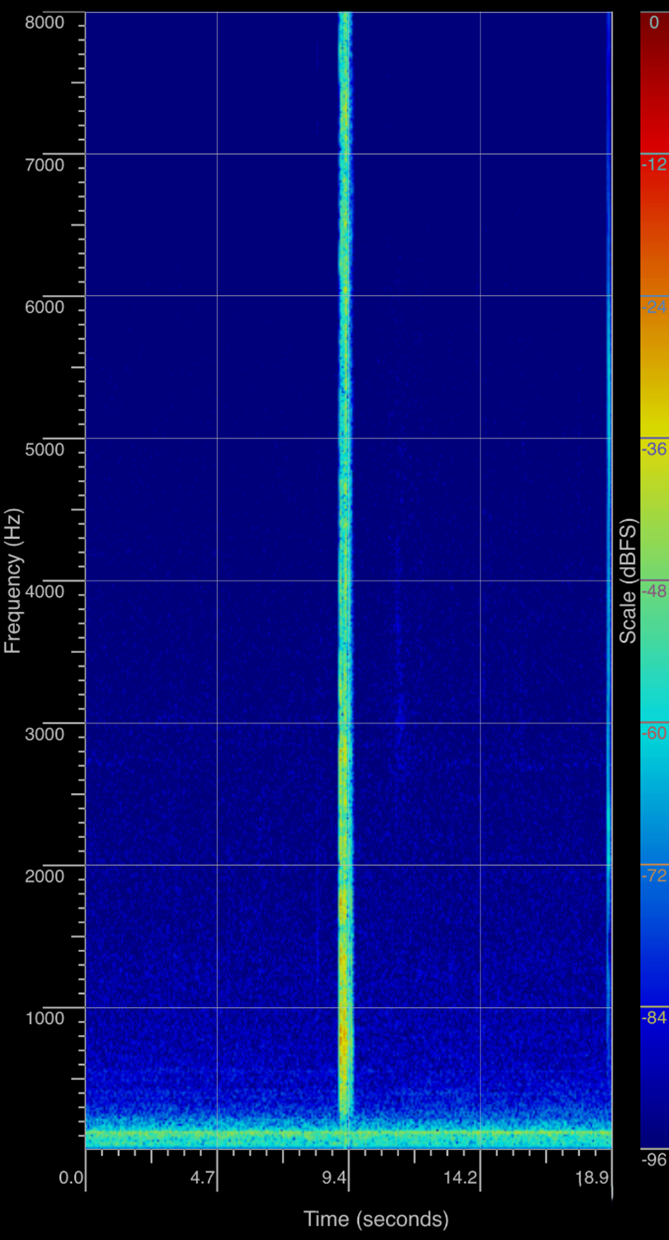

Illustration 2: Spectrograms

of the generated sounds of Coloring-Pencil and Dropping-Keys-on-Table[1]

‘Representation’ and Sound

Representation serves the ‘dogmatic image of thought’ as that which categorises and judges the world through the administration of good sense and common sense, dispensed by the autonomous, rational and well-intentioned individual, according to principles of truth and error. (MacLure, 2013, p. 659)

‘Representation’ relies on the readymade and therefore confines the world. Life nonetheless never restricts itself to that which is categorizable. In fact, there are aspects of living that evade spoken and written language all together. Sound is one such aspect that resists the tidiness of linguistic labeling.

Yet, there it is. Sound hides in fieldnotes. Sound hides in activities, as effects. “Constrained within the boundaries of what is traditionally considered to count as data”, Mazzei (2003, p. 357) finds herself looking primarily at texts and the spoken word in empirical materials before conceptualizing new ways of ‘listening’.

The process for listening to silence did not conform to the conventional constraints imposed in a traditional analysis and interpretation of empirical materials. Listening to silence didn’t “happen” as observation in the way we as researchers, or at least this researcher, had been trained to gather and analyze empirical materials but instead was revealed over time and was a result of careful, patient listening both during and after the conversations. This empirical material was not always observable or immediately “present” but rather was discovered in the hidden, the covert, the inarticulate: the gaps within/outside the observable (Mazzei, 2003, p. 358)

Listening to silence is thus not “a desperate attempt to make something out of nothing” Mazzei argues (2003, p. 358). It is instead a ‘patient listening’ that takes hold of what sits in the ‘gaps’. I conceive this patient listening as ‘staying with’ the real. It is the labor of refusing to hasten through and labeling with words. But then again, “[m]ethod is much less assured in dealing with quasi-linguistic stuff such as […] silence, and all the tears, sneers, sighs, silences, sniffs, laughter, snot, twitches or coughs that are part of utterances”, MacLure says (2013, p. 664). And perhaps it is as simple as that, we are more comfortable with language, preferably the written word, and less sure what to do with that which comes without a name and that which is difficult to point at. But being content with what is comfortable is not enough, I propose. We must poke wounds and unsettle the already shaken. A way to do so is to get rid of ideas about re-presentation and move on to presentation.

An examination now of what is hiding in notes together with a look at the introductory illustrations (Illustration 1 and 2) to examine how ‘making sounds seen’ might be one way of moving past dogmatic re-presentation.

Theme I – Wordless Voicelessness

The sound of the art class is best described as quiet. But ‘quiet’ is not silent. Nor does quiet capture the ambience of the art class. In fact, each word I try merely confuses matters further. Each word I try makes quietness turn invisible.

The world of sound is primarily one of sensation rather than reflection. It is a world of activities rather than artifacts, and whenever one writes about sound or tries to graph it, one departs from its essential reality, often in absurd ways. (Schafer[2], 2007, p. 84)

The sound of the art class does indeed step into ‘absurd’ costumes as I try communicating its muteness.

Nevertheless, it is lexical signs in already wordy notes that make quietness come into view. Every now and then a word signals that quietness still prevails: ‘calm’, ‘calmly’, ‘silently’, ‘complete silence’. But words fail to convey the sound’s components, fail to relate its duration. To be precise, selected words describe the volume and pulse of the arts class sound, at best. We must therefore continue poking.

The Duration of Wordless Voicelessness

It is false to say that the art class is ‘silent’, as in soundless. A notation at 10.10 reads: “The pupils are working, a food cart is heard rolling by, pencils are selected and placed on a desk, the scratch from coloring is faintly heard” (T, p. 4). Listed activities make sounds, albeit subdued sounds. In fact, there is no such thing as silence, as the composer and philosopher John Cage states:

There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time. There is always something to see, something to hear. In fact, try as we may to make a silence, we cannot. For certain engineering purposes, it is desirable to have as silent a situation as possible. Such a room is called an anechoic chamber, its six walls made of special material, a room without echoes. I entered one at Harward University several years ago and heard two sounds, one high and one low. When I described them to the engineer in charge, he informed me that the high one was my nervous system in operation, the low one my blood in circulation. Until I die there will be sounds. And they will continue following my death. (Cage, 1973, p. 8)

Sounds are. Always. Duration itself, when it comes to it, manifests through sound. Put differently, perceiving sound is a materialization of time passing. Duration entails spatialized soundwaves which give an acoustic rendition of time passing during the art class. One can consequently never escape sound. So, when it comes to the quietness of the art class, it is accurate to say that it lacks the spoken word. The lesson must thus be described as wordless. But how present wordlessness?

Whiteness

We have against all odds detected voicelessness in wordy notes, the challenge is next to write a voicelessness that it also utterly wordless. It seems that the only way to do wordlessness any justice is through the white page, or white screen (see Illustration 1).

Wordlessness presented through whiteness has the heard transformed to the observable:

Truth, we think, must be observed by the "eye," then judged by the "I." Mysticism, intuition, are bad words among scientists. Most of our thinking is done in terms of visual models, even when an auditory one might prove more efficient. We employ spatial metaphor even for such psychological states as tendency, duration, intensity. We say "there- after," not the more logical "thenafter"; "always" means "at all times"; "before" means etymologically "in front of"; we even speak of a "space" or an "interval" of time. (Carpenter & McLuhan[3], 1960, p. 66)

Space rather than sound, the visual before the aural; yet, how difficult it is to keep one’s gaze on page whiteness. Perhaps we ought to add ‘the written word rather than whiteness’ to our list of preferences. How well behaved our gaze is as it skims the surface for words to rest on. Staying with the whiteness of the page or screen, conversely, is exhausting. Thus, in Illustration I the visualization of art class wordlessness is under the threat of the small font that lures in the left corner below that reads: “Illustration 1: Wordless Voicelessness”. But without the caption, whiteness would risk being brushed off as a mere layout mistake.

The duration of white page and screen wordlessness has now been transposed into Euclidean logics. In this move, voicelessness has transformed to what Carpenter and McLuhan (1960) speak of as something ‘observable to the eye’. Wordlessness voicelessness materialized as a white page or screen turns the aural touchable, measurable, and even ‘judgeable by an I’.

Theme II – Coloring-Pencil and Dropping-keys-on-table

Theme I on a silence moves art class ambience beyond depictions of volume to specifying it as ‘a wordless voicelessness’. But for wordlessness to move beyond a ‘lack’ (of voice and words) as the proposed sound – “try as we may to make a silence, we cannot”, as John Cage put it (1973, p. 8) – we must turn our attention to voicelessness as the conditionfor other sounds. The second theme on a silence therefore examines how voicelessness paves the way for other relations to be heard. Here too, the inquiry goes hand in hand with problematizing the challenges of writing wordless sound.

Let us imagine sound was captured through a recorder and played back as an audio file. The played- back sound would still never be an exact re-presentation that corresponds to reality, as even the best device will come to affect the reality it seeks to represent by the fact that it performs a sound cutout. The question also remains of how to distinguish between still nameless sounds when writing about a particular sound-affect and its effects. It is safe to say that it takes effort to maneuver sounds past conventional sign systems in investigated assemblage[4]. Illustration 2 nonetheless experiments with spectrograms to examine supplementary options to written language when exploring sound.

Spectrograms and Language – Synthetization

The spectrogram displays sound over time on the horizontal axis, and frequency on the vertical. Sound manifests as a visual pattern that communicates one version of the sound story, this time through waves. Coloring-pencil and dropping-keys-on-table are sounds encountered in the arts class but enacted and recorded post situ to be displayed as spectrograms[5]. The two sounds are examples of sounds from the arts class that come forth through voicelessness. To see the wave-stories and the different textures, colorings, amplitudes and durations, see Illustration 2 about coloring-pencil and dropping-keys-on-table.

But instead of thinking spectrograms or language, I propose wave-patterns and words. The visualizations combined with my reading of the spectrograms enable synthetization and exploring additional sides of the arts class sound. Now to synthetization.

As I return to Illustration 2 and look at coloring-pencil-on-paper, I see the subdued and consistent sonic mat that forms a soft backdrop to the space-time. The wave-pattern displays the timidness of pencil-tips rapidly and repetitiously brushing on paper (Illustration 2, left spectrogram). Dropping-keys-on-table makes a key attack where turquoise-green perforates the deep blueness. Green-frequency makes a fierce cut into a dark blue universe (Illustration 2, right spectrogram).

Art Class Sound Milieu

Voicelessness lets peripheral and soft sounds from the relation between a hand, a coloring pencil, and a paper, come forth, together with another nexus of relations where a hand abruptly ends its relation to a set of keys, and a table takes over. But sound is not just simply a backdrop orchestrated by becoming- teacher during an art class. Rather, assemblage ambience enfolds collectively formed soundwaves that bounce off hard tables, thin papers, and paper-clothed walls, before becoming absorbed by the heated textiles on warm fleshy bodies. As room temperature and autumn rain amalgamate with sweaty bodies, sound soon melds with scent to form a singular assemblage universe, a milieu. This ‘milieu’ is the heterogenous block of space-time that has gone through a process of coding and the milieu and its sounds have attained meaning (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987), as it has become ‘artclass’ (more about ‘milieus’ and ‘coding’ in mosaic Quizzing).

Coloring-pencil sound and dropping-keys-on-table sound are monitored as familiar and contextually predicable sounds to the class. Sound predictability and the control of sound are factors that make sounds less distracting and annoying (Kjellberg et al., 1996[6]). I take the liberty to speak about said research through a Deleuzian perspective by proposing that what Kjellberg et al. (1996) are pointing at is how the effects of sound-affect pertain to assemblage relations. Children’s monitored indifference to the startling sound of key-clinking, and the later even more intrusive sound of food-cart rolling, would in keeping with Kjellberg et al. (1996) be just another way of saying that it is a sound they understand. Key-clinking-affect demonstrates assemblage territoriality[7] – the class does not flinch since they understand and find the sound familiar, whereas I, surprised, jump on my chair (more about territoriality in the mosaic Quizzing).

Making Sounds (Un)Seen

What does the challenge of writing sound have to do with ‘how encounters unfold and with what effects´? As I suggest, mapping proposes that sound encounters are a pivotal, yet ephemeral, element in the formation and maintenance of school milieus, and this is why it becomes important to find ways to write sound.

To sum up, a short overview of what has been proposed is in order. Voicelessness is not something that can be related only to an individual, just like sound it is instead a joint effort that characterizes the entire art class assemblage. Sound is more than a backdrop. The effects of voicelessness in the mosaic Park of Silence, illustrate how an assemblage retorts to alternative means of communication in order to secure voicelessness. Or perhaps it is the comforting sounds of coloring-pencil and dropping-keys-on-table they desire? Why not go and experience the sound for yourself in mosaic Coloring-Pencil Sound! For ‘voicelessness’ has been shown to be something other than ‘silence’, since there is no such thing as silence, as Cage (1974) has taught us. If we instead conceived of voicelessness as a condition for other activities and relations to be known,then voicelessness together with coloring-pencil and dropping-keys-on-table are proposed as themes on a silence. Sound, it seems, is one of many answers to the question of what affects becoming- teacher during a workday. Thus, if sound is central for becoming- teachers, we need ways to detect and write sound to better examine its effects.

It has been shown how sounds are difficult to present through written language since voicelessness is wordless. We must therefore resist the reductive practices of labelling sound into predefined categories, just as we ought to try to stay with the challenge of reporting the duration of sound – such as forty-three minutes of voicelessness. This is to say that one answer to ‘what affects the reports of sound-encounter effects’ is language, perhaps specifically written language. Inquiring therefore relies on developing strategies that reduce written-language-affect in writing about sound. The ‘whiteness’ of a page or screen, together with ‘spectrograms’, are therefore suggestions of ways to convey the specifics of sound stories. To further examine how sound works, go to mosaics Park of Silence and Coloring-Pencil Sound.

References

Cage, J. (1973). Silence: lectures and writings. Wesleyan University Press.

Carpenter, H. & McLuhan, M. (1960). Auditory space. In: Carpenter E., & McLuhan M. (eds.) Explorations in Communication. Beacon Press, 65–70.

Deleuze, G. ([1966]1988). Bergsonism. Zone.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. ([1980]1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Kjellberg, A., Landström, U. L. F., Tesarz, M., Söderberg, L., & Akerlund, E. (1996). The effects of nonphysical noise characteristics, ongoing task and noise sensitivity on annoyance and distraction due to noise at work. Journal of environmental psychology, 16(2), 123-136.

MacLure, M. (2013). Researching without representation? Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology. International journal of qualitative studies in education, 26(6), 658-667.

Mazzei, L. A. (2003). Inhabited silences: In pursuit of a muffled subtext. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(3), 355-368.

Schafer, R. M. (2007). Acoustic Space. Circuit, 17 (3), 83–86.

Verstraete, P., & Hoegaerts, J. (2017). Educational soundscapes: tuning in to sounds and silences in the history of education. Paedagogica Historica, 53(5), 491-497.

[1]With permission from ©2019-2021 Oxford Wave Research Ltd.

[2]Schafer discusses sound and the challenges of representation. In this discussion he also problematizes, what I take as, the clash with the conventions of the written word when he in recollecting a conference writes: “for several days I saw slides and heard papers on various aspects of aircraft noise without ever once hearing the sonic boom that was the object of the conference” (2007, p. 84). These observations about ‘sound’ point at the challenges in trying to ‘represent’ sound. However, Schafer, the proposed originator of a field within sound studies called ‘educational soundscapes’, represents what is taken as a ‘prescriptive stance’ on sound and silence where education is to teach people how to handle increasing sound levels so that people can build ‘meaningful lives’ (Verstraete & Hoegaerts, 2017). In a special issue on ‘educational soundscapes’, Verstraete and Hoegaerts write: “Schafer’s ideas about soundscapes thus clearly imply a belief in the possibility of authentic selves: after having learned how to deal with our sonic environments people would be freed and again able to become themselves” (2017, p. 494). Verstraete and Hoegaerts abandon Schafer’s idea about ‘authentic selves’ in favor for what the editors articulate as “how [acoustic realities, sounds as well as silence] have played a part in establishing, revising, and renewing processes of subjectification throughout the course of western history” (2017, p. 494). Consequently, whilst Schafer makes important observations about the impact of sound, that sound matters in educational contexts and about the complexity of representing sound, ideas about ‘authentic selves’, conversely, together with the prescriptive approach associated to the meaning of sound (silence), diverge from the stance in this project.

[3]There are several points made in Carpenter and MacLuhan (1960) that relate to this inquiry. Firstly, the merger of ‘sound’ (as acoustics) and ‘space’, and the way the quote also addresses the tension between ‘science’ and ‘intuition’. In later sections, the authors also take on the ‘durational’ dimensions of sound as ‘being’ [or, rather: “it be” ([italics in original] Carpenter & MacLuhan, 1960, p. 67)]. In several passages Carpenter and MacLuhan also highlight the power of language related to thought, via the dogmatism of the ocular (1960). This inquiry entering the ‘sound-scene’ through the perspectives of the anthropologist Carpenter and the media theorist MacLuhan, also serves to foreground related concerns discussed by Deleuze’s Bergson (Deleuze, [1966]1988). In fact, the appreciation of Carpenter’s work on the aural is explicitly acknowledged by Deleuze and Guattari in a passage discussing nomads as “vectors of deterritorialization”; here they reference said writer in a segment about ‘haecceities’ that speak of space as “a tactile space, or rather "haptic," a sonorous much more than a visual space” ([1980]1987, p. 382). Carpenter bringing together ‘sound’ and ‘space’ can be seen in the footnote to the quoted section where his work is described as offering “admirable descriptions […] of the ice desert […] in Eskimo (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1964): the winds, and tactile and sound qualities; the secondary character of visual data, particularly the indifference of the nomads to astronomy as a royal science; and yet the presence of a whole minor science of qualitative variables and traces” ([italics in original] Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 557).

[4]This is a sweeping and normative statement. Whether or not research admits other forms and formats is linked to research field and the body under investigation. Take for instance artistic and performance research or for that matter digital and technological strands within the field of education where there are alternative modalities to distribute research through that allow digital formats. However, written texts, preferably articles, belong to the language of research and what Deleuzoguattarian thinking discusses as the ‘The Royal Sciences’ ([1980]1987)). But, there are of course platforms where sound in its aural format is treated as a ‘science’ and where sound does not have to shed its singularity as soundwaves in order to attain legitimacy; see for instance the peer-reviewed online platform Seismograf Peer (https://seismograf.org/peer (the platform is hosted by Seismograf, a Danish magazine supported by the Danish Arts Council, Danish Composers’ Society and Independent Research Fund Denmark ‘). In an issue from April of 2021 the focus is “Sounds of Science: Composition, recording and listening as laboratory practice.”

[5]The choice not to use audio-recorders is linked to ethical, practical, and onto-epistemological considerations. Relations are in focus in this project and the affect that propels these relations. Sound is thereby one of multiple and concurrent affects produced in mapped relations, as opposed to investigating sound per se. Keys clinking on a table on the other side of the room is thus one body amongst many that participate in the making of art class-‘assemblage’.

[6] Even though Kjellberg et al. (1996) speak from an entirely different onto-epistemological strand, and even though their main objective is to say something about the relation between noise and its effects on work, the implications of their line of reasoning are interesting for the project at hand (see the above discussion).

[7]In this proposition I make a rather big leap as I propose a comparison between the sudden noise of key-clinking to a study that investigates “[f]actors influencing the subjective responses to noise” through questionnaires combined with a noise measurement of each person’s workplace (office, laboratory, and industry) (Kjellberg et al., 1996, p. 123). The study explains forming ‘an annoyance’ and ‘a distraction’ index based on factor analysis, where the ensuing results illustrate that a sound’s ‘predictability’ and ‘controllability’ influence how sounds are perceived (Kjellberg et al., 1996). What I find interesting is not merely that these factors influence, but that predictability and controllability speak about bodies repeated association with sounds that become familiar. Said differently, sound is another relation within an assemblage milieu and these relations materialize as the effects of sound-affect.