Doorway Peekaboo

Initial

contact;

Disappearance;

Reappearance;

Re-established contact.

[…] What the child appears to be learning is not only the basic rules of the game, but the range of variation that is possible within the rule set. It is this emphasis upon patterned variation within a constraining rule set that seems crucial to the mastery of competence and generativeness.

(Bruner & Sherwood, 1976, p. 283)

‘Initial contact’, like becoming-teacher greeting a class. ‘Disappearance’, like a class being sent away to do groupwork in adjacent rooms. ‘Reappearance’, like becoming-teacher checking in on groups working. ‘Re-established contact’, like a class returning to the classroom for assembly. The pattern is familiar, the rules simple. We learn early on the repeated pattern where the disappearance of an adult promises its return; through peekaboo first, and then again through institutional games such as groupwork. Let us bring a somewhat dated empirical study along (Bruner & Sherwood, 1976) into our thinking as we enter the events of a becoming-teacher introducing an assignment involving groupwork.

Examining ‘how encounters unfold and with what effects’, this mosaic investigates the circumstances of a becoming-teacher’s movements between different spaces during a lesson. The events we step into involve becoming-teacher introducing an upcoming ‘chewing gum test’ and the necessary preparations the class needs to do in smaller groups.

Before joining this becoming-teacher’s lesson, we will briefly re-visit all the observed lessons from the sixteen becoming-teachers in this inquiry, to see how bodies move between spaces during lesson time.

Threshold Crossing

Sixty-four lessons have been mapped during the work with this thesis. Twenty-one of these lessons involve a becoming-teacher moving seven times or more to and fro a classroom during lesson time[1]. Repetitive threshold crossing always unfolds in a nexus of singular events, but what eighteen of these lessons share is that these movements are the effect of lesson activities organized as ‘individual work’ in different spaces, or (like here) as ‘groupwork’ in different spaces[2].

The frequency of threshold crossing is thus closely tied to choice of activities and space layout. When lesson activities are designed as individual work in different spaces, becoming-teachers cross thresholds between seven and up to thirty-two times during one lesson. When lesson activities are designed as groupwork in different spaces, then becoming-teachers cross thresholds from ten up to thirty-six times, which is the case with this becoming-teacher where planned activities involve children being distributed into three different spaces.

A visit now to the site where a becoming-teacher is about to begin what comes forth as a thorough workout.

Chewing Gum Test

It is 12.11 and becoming-teacher and a class of sixteen are back from lunch. The group is told that in today’s lesson they are to prepare for tomorrow’s science class. Becoming-teacher says it is going to be ‘a chewing gum test’, whereupon children instantly begin buzzing and sending quick smiles to one another in what looks like excitement.

12.16, What kind of tests can you do with chewing gum? Becoming-teacher asks. If it tastes like what it says, a child proposes. How long the taste lasts, someone else says. How many you can fit in your mouth a third suggests. To this becoming-teacher intervenes and says, No, not that one. You won't have that many gums. How well you can make bubbles, a new suggestion goes. How big bubbles, someone adds. (N, p. 7)

Four minutes later, becoming-teacher instructs the class that they are to work in groups and create a word document where they are to specify their chosen materials. They start collectively and different voices begin naming materials for becoming-teacher to insert into their shared list projected on the canvas screen:

Mouth! someone calls. Teeth! another voice says. Chewing gum! Stomach! To which becoming-teacher interrupts explaining, No, you can’t swallow.

Ruler! a new voice proposes. A lever!, someone adds. A lever? Becoming-teacher asks. Yes, if you want it to be launched into the air, the child explains. (N, p. 7)

Becoming-teacher writes all suggestions into the shared document and the children read. Letter by letter appears on the large screen before the children seated on a sofa, a carpet, on pillows, and on top of enormous bean bags.

As becoming-teacher is writing, a child suddenly interrupts:

The child points at something becoming-teacher has missed. What? becoming-teacher asks. The child explains, You can't chew before you put the gum in your mouth! referring to the bullet list under the heading "How can we do this". The list reads:

1. Begin chewing

No, you're right about that, becoming-teacher says and corrects the list.

[Revised list:]

1. Put into mouth

2. Begin chewing

(N, p. 7)

Before they part, they briefly discuss viable scales for assessment for tomorrow’s tests. A child suggests they use their grading system, which becoming-teacher agrees is a good suggestion before adding that their results must be visualized in tables. The introduction ends at 12.36.

Groupwork in Three Different Spaces

The objective for upcoming groupwork is accordingly to finalize their preparations for tomorrow’s chewing gum test. In groups children disperse into three spaces assigned by becoming-teacher. At the same time becoming-teacher’s supervisor enters together with a classroom assistant. There will thus be three adults present for parts of the lesson: becoming-teacher, supervisor, and an assistant.

A look at the space

layout of the three spaces (see Illustration 1):

Illustration

1: Space layout

Space I and III in Illustration 1 are separated by a wall with a partial glass section and a door. Space II is a few steps away from space I[3].

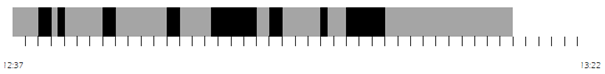

Children disperse into the assigned rooms and becoming-teacher visits each group to ensure that everybody knows what to do. However, the first round automatically instigates a second, third, and fourth round. But how frequent are the visits, and what is their duration? This can be visualized in a time diagram, registering the disappearance-reappearance intervals from the perspective of the children seated in each space. The scales below the timelines indicate each minute passing. Grey fields illustrate when becoming-teacher (BT) disappears, and children are left to their own devices to do groupwork. Black fields illustrate when becoming-teacher reappears.

BT disappearance

BT reappearance

Space I

Space II

Space III

Illustration 2: Disappearance and Reappearance Intervals Space I, II, and III – Child Perspective

The group in space I gets fourteen visits before assembly. Twelve of these visits take one minute or less. The group in space II receives eight visits, whereof six take one minute or less. The group in space III gets twelve visits. Eleven of these take one minute or less.

Accordingly, the group seated in space I get a few more visits than the other groups, which seems reasonable since this is a space becoming-teacher needs to pass in order to reach space III. It is also possible to see that five visits in total, all spaces taken together, are allocated two minutes or more. Does the difference in interval affect unfolding events? Let us take a closer look to explore the effects of the above disappearance-reappearance intervals.

Doorway Peekaboo

In the first round, becoming-teacher makes sure everybody knows what to do. But circulation continues, and with everybody working it is no longer obvious why becoming-teacher keeps reappearing. Another option also dismissed is allocating one adult per space, which could be possible considering that the supervisor and assistant have joined and stay for much of groupwork. Instead, whilst the supervisor and the classroom assistant take a laidback role and remain primarily in space I and III observing the children work from afar, becoming-teacher keeps circulating making visits to all three spaces. This begs the question, what or whose needs does circulation serve?

The disappearance-reappearance pattern in the above timelines (see, Illustration 2) shows how becoming-teacher, a few minutes in, takes peeks that last less than a minute. At one point, becoming-teacher manages to peek into all three spaces within one minute. The many brief visits mainly entail observing the children while answering and/or asking them questions. As becoming-teacher answers and/or asks questions, reappearance now begs for reciprocity. Peeking thus moves from being a one-sided activity involving becoming-teacher observing, into a doorway peekaboo – a game that involves two parties.

Epistemic Dislocation

Doorway peekaboo nestles into science groupwork and in so doing, changes the logics of ‘groupwork’. Groupwork understood as ‘the reciprocal utilization of children’s collective resources’ for the purpose of finalizing preparations for tomorrow’s tests, becomes dislocated through doorway peekaboo. It is no longer primarily the joint efforts of children working collectively on a problem that steers the process, but rather answering and/or asking pre-maturely articulated questions in keeping with a pulse set by the reappearing becoming-teacher.

Now, the point is not whether groupwork becomes better or worse through doorway peekaboo, the question at stake is detecting that the rationale of groupwork changes; ‘solving problems collectively in a pace set by the problem at hand’ as the underlying principle, shifts into the related albeit different logic of being ‘able to ask and/or answer questions when someone outside problem-solving says so’. Generic questions articulated by someone outside the problem now steer children’s problem solving. Again, one cannot know howthe learning process changes through the intervention of becoming-teacher’s presence, only that it does change.

Patterned Variation

Insignificant as the above shift may seem, its epistemic effects are considerable. Doorway peekaboo builds in a wait-and-release element where becoming-teacher’s disappearance-reappearance intervals may come to overshadow the science problem, or so unfolding events suggest as a child in space I begins surveying becoming-teacher’s whereabouts. Each time becoming-teacher walks away, the child shifts to watch YouTube clips. The child’s awareness is carefully attuned to becoming-teacher’s disappearance-and-reappearance intervals. The child actualizes a YouTube-and-work pulse that aligns perfectly to becoming-teacher’s doorway peekaboo. The event now begs the question: Is the child’s defiance the proof of becoming-teacher’s need to do doorway peekaboo, or is the child’s defiance the result of doorway peekaboo?

We may recall what Bruner and Sherwood’s study about parent-child peekaboo proposed: “What the child appears to be learning is not only the basic rules of the game, but the range of variation that is possible within the rule set” (Bruner & Sherwood, 1976, p. 283). Could it be the same here, that children learn doorway peekaboo and thus try to figure out ‘the range of variation possible within the rule set’ of peekaboo, rather than science. Stated differently, does doorway peekaboo dislocate the learning objective, from learning science to learning peekaboo?

It is, Bruner and Sherwood suggested, “this emphasis upon patterned variation within a constraining rule set that seems crucial to the mastery of competence and generativeness” (1976, p. 283). Following this line of reasoning, a child adjusting YouTube-and-work intervals in synchronization with those of becoming-teacher, is a child that has reached a ‘mastery of competence and generativeness’ of how to live school life by modifying one’s actions in keeping with teacher gaze.

Groupwork and Control

Doorway peekaboo thought through the Deleuzoguattarian concepts territorialization and refrain helpproblematize what is going on during groupwork. ‘A refrain’, such as doorway peekaboo, enacts a groupwork ‘territory’ by marking a circle that serves “to organize a limited space” (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987, p. 311). Groupwork through doorway-peekaboo refrains territorialize both becoming-teacher and children by imposing order into the chaos of bodies being scattered into different spaces. Yet, children and becoming-teacher become territorialized differently[4].

The point of thinking ‘refrain’ is that it reminds us that repeated acts such as circulating between rooms initially may serve to stabilize chaos, but they can later cause the territory to draw a ‘line of flight’; in other words, have a simple act hide radical change (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987). A doorway peekaboo that begins as a way to help children get to work, may if excessively repeated distort pedagogical objectives into a form of control of bodies.

The distortion of pedagogical objectives is not intentional. On the contrary, circulation is enacted as a response to a specific wall configuration and the becoming-teacher’s inability to see the children. Refrains help illustrate how acts come to territorialize ‘blocks of space time’. Because groupwork codes mundane acts like ‘talk’ and ‘walls’ in particular ways, that is, in the light of groupwork the effects of talk- and wall-affect attain certain meaning (Deleuze & Guattari, [1980]1987). Talking to one another is not a problem with the appropriate walls in place. But walls that stop talking from disturbing other groups, are also the same walls that make them go out view from becoming-teacher who is responsible for said groupwork. And not being able to see all children is within the logic of groupwork something becoming-teacher solves through circulation.

But let us one last time turn to the excerpt about parent-child peekaboo. What if groupwork has both child and becoming-teacher trying to figure out patterned variation in the simple interplay of disappearance and reappearance; when the ‘chaos’ of not seeing children threatens, disappearance-and-reappearance becomes the territorializing refrain that creates ‘a sense of order’ through seeing – whilst children explore alternative ways of how to deal with becoming-teacher control.

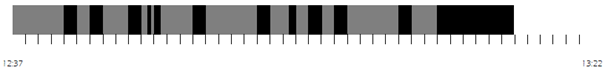

The timelines (Illustration 2) above illustrate how groupwork appears from the perspective of children seated in three different spaces. But we can also look at the visits to the groups from the perspective of becoming-teacher:

Illustration 3: Observation Intervals in Space I, II, and III – Becoming-teacher Perspective

As we can see, groupwork territorializes becoming-teacher and children differently; the merged timeline (Illustration 3)illustrates becoming-teacher’s circulation not as an oscillation between disappearance-reappearance but as a continuous enactment of observing-asking-answering(solid black mid-section). Put another way, becoming-teacher desires seeing. So, when children try focusing on science, becoming-teacher focuses on controlling that they do science.

One of many answers to the question of ‘how encounters unfold and with what effects’, is that the encounter with groupwork instigates the enactment of control. Groupwork has children allocated into different spaces which hinders continuous visibility. Movement, consequently, becomes the solution to preserve visibility and control:

[Foucault] was actually the first to say that we’re moving away from disciplinary societies, we’ve already left them behind. We’re moving toward control societies that no longer operate by confining people but through continuous control and instant communication. […] One can envisage education becoming less and less a closed site differentiated from the workspace as another closed site, but both disappearing and giving way to frightful continual training, to continual monitoring[…] of worker-schoolkids or bureaucrat-students. They try to introduce this as a reform of the school system, but it’s really its dismantling. In a control-based system nothing’s left alone for long. (Deleuze, 1995, p. 174-5)

While the transition from disciplinary societies to societies of control is most apparent in questions related to the development of technology and digitalization, it might nevertheless be that the entrainment in continuous visibility and communication penetrates even the analog sides of life. As life both in- and outside educational settings habitually relies on continuous visibility and control, why would activities that build on groupwork be any different? The question is what the need to see and control does to bodies’ problem-solving capacities.

References

Bruner, J. S. (1975). Peekaboo and the learning of rule structures. Play: Its role in development and evolution, 277-285.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. ([1980]1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. (1995). ‘Control and Becoming’. In Negotiations 1972–1990 (pp. 169-176). Columbia University Press.

[1]The twenty-one lessons are distributed amid nine of the sixteen becoming-teachers.

[2]Three of the twenty-one deal with instances where a becoming-teacher engages in their own preparations while assisting a colleague or going to a colleague’s classroom for a joint movie session. Of the remaining eighteen lessons, twelve involve ‘individual work and spatial distribution’, six involve ‘groupwork and spatial distribution’.

[3] Space II (Illustration 1) is so small that becoming-teacher can remain in the doorway and still see what the group is working on. This means that the threshold from space I into the hallway always also includes becoming-teacher peeking into space II without having to cross a second threshold. In short, there are as many thresholds as there are rooms.

[4] In Deleuzoguattarian ([1980]1987) thinking, children and becoming-teacher belong to different milieus.